Editorial note:

Since the publication of this original analysis, the Submetaphysics framework has undergone substantial refinement—particularly in the domains of ontology, moral evasion, typological drift, and vertical discourse. In order to preserve continuity and accessibility, this initial version remains intact. It still functions as a concise introduction and contains several useful case studies.

The revised Overton analysis no longer treats drift as a cultural or political phenomenon alone, but develops it into a full ontological-moral, semiotic, and theological architecture—explaining why drift occurs, why populations accept it, why institutions perpetuate it, how it is enforced, and why God ultimately interrupts it.

A fully revised and architectonically integrated edition, reflecting developments, is available here:

▶ Access the Revised Overton Window Analysis

The Overton Window—a term coined in the 1990s by policy thinker Joseph P. Overton—describes the range of ideas considered socially and politically acceptable at any given time. While initially used to analyze legislative feasibility, it has evolved into a diagnostic of ideological atmosphere and discursive constraint—a spectrum that governs what may be spoken, endorsed, or challenged without social cost.

But the Overton mechanism goes deeper. It controls referents, not merely words. It governs the typological field—determining which moral and theological categories retain public legitimacy and which are delegitimized, reassigned, or erased. That makes it not merely a social phenomenon, but a semiotic and ontological instrument. As such, it extends the very dynamics explored in our prior sections on semiotics and pragmatics—now manifesting at the societal level, where typological drift and discursive manipulation shape not only words, but what may be meant.

Some refer to this system—informally but not inaccurately—as “the matrix” or “the network”; others more vaguely speak of “they”. What they intuit is real: a system that governs not the substance of reality, but the visible and speakable spectrum of it.

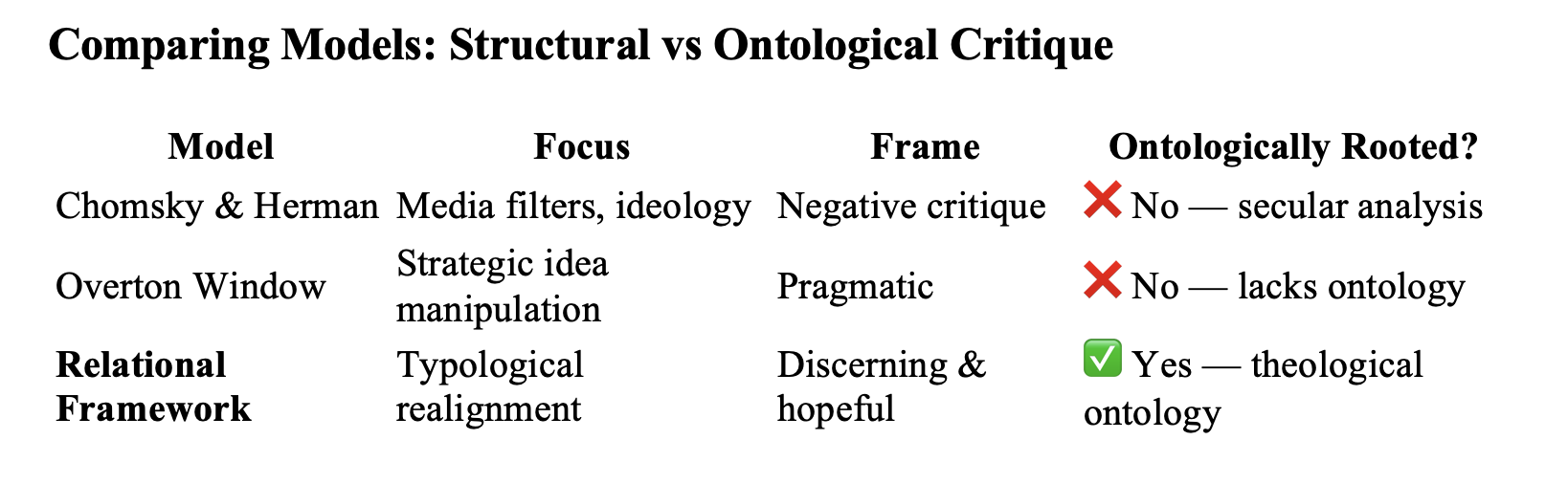

Although this dynamic has been dramatized in fiction, exposed partially in media critique (e.g., Chomsky and Herman’s Manufacturing Consent), and felt by many, it remains under-theorized at the levels of:

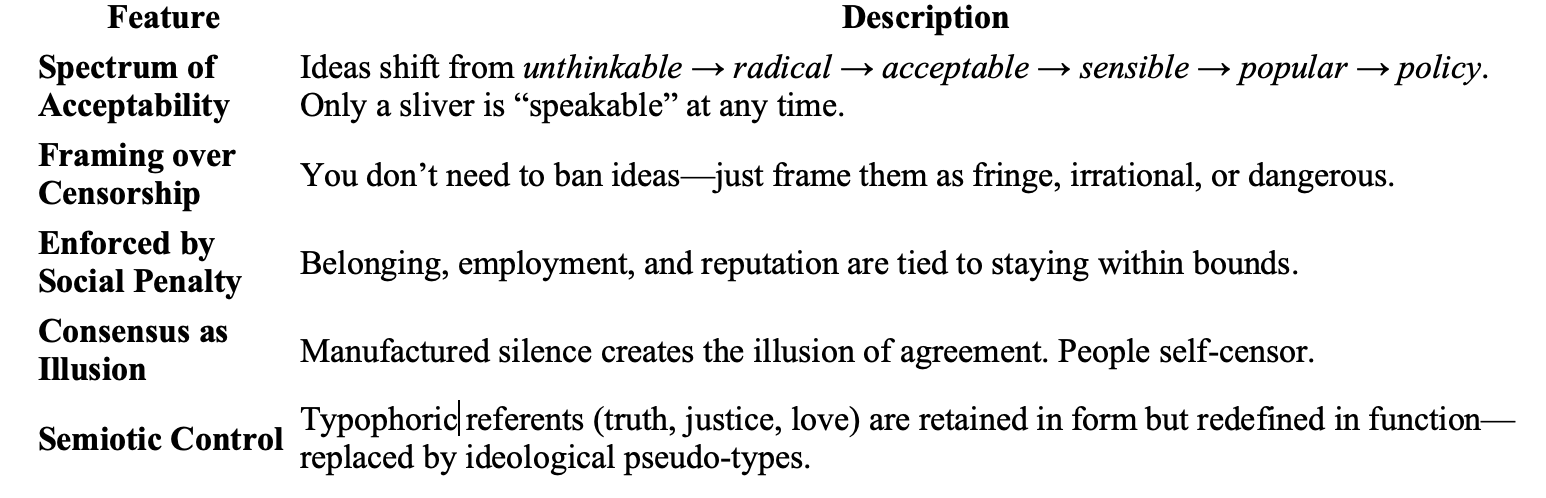

This relational-theological model seeks to fill that gap: offering not a reactionary posture, but a hopeful and principled response rooted in typology, divine reference, and covenantal accountability. Overview of the Overton model is as follows:

This process is not accidental. It unfolds in deliberate, trackable phases, each with psychological, institutional, and theological consequences.

Discernment: This is pre-argument. No proposition has been offered—only presence. In semiotic terms, this is ontological disassociation via imaginative priming. The pseudo-type is introduced through emotional familiarity, bypassing rational consent.This is not merely cultural suggestion—it is an attempt at discursive pseudo-instantiation, where a fabricated type is introduced as if it were legitimate, bypassing the divine prerogative to define what kinds of being may exist. It sets the stage for later pseudo-tokens to appear—instances of that unauthorized type treated as morally real and socially obligatory.

Discernment: Typophoric terms are retained but their referents are reversed. This constitutes a symbolic inversion—the outer form of the word remains, but its ontological root is reassigned. The battle is not over facts but what the word refers to.

Discernment: This stage replaces reasoning with presupposition. Discursively, it marks the closure of debate through assumed convergence. Theological dissent is re-coded as regressive, despite no ontological consensus having occurred.

Discernment: The mechanism here is pseudo-dialectic. Framing tools like endophoric deixis (“this is compassionate”) create phantom consensus, assuming moral clarity without referential inspection.

Note: Controlled debates often operate by debating the token level of reality (e.g., “Should this person be affirmed?”) while forbidding examination of the type being claimed (e.g., “Is this kind of being real?”). This is a form of ontological deferral, where the pseudo-type is treated as settled and the focus is shifted to downstream consequences.

Discernment: The legal typology is reversed: Truth becomes harm; conscience becomes offense; moral inversion occurs: what was once seen as conscience is reframed as offense; what was once transgression is recast as identity. This is institutional typophoric inversion.

Discernment: This is not erasure but typological replacement. The new meaning is projected backward, rendering resistance not just wrong but perverse.

Discernment: The scapegoat may be sincere, but their function becomes symbolic within the system—offering catharsis without systemic repentance. Ask: Did it return us to something ontologically real—or merely reroute the narrative? Did it restore moral clarity, or just offer symbolic relief?

Chomsky and Herman (1988) rightly observed that control is not about silencing dissent—but about pre-limiting the range of debate while showcasing vibrant disagreement within the permitted spectrum.

This dialectic functions through several converging tactics:

The relational-theological framework developed here does not respond to the Overton system with fear, tribalism, or despair. It does not idolize tradition for its own sake, nor does it reflexively reject modernity. Instead, it calls for reverent clarity—a discernment rooted in the conviction that every word, symbol, and moral claim must be traced back to its ontological referent and tested for typological fidelity to God’s revealed order.

One of the most subtle tactics in Overton manipulation is the exploitation of deixis—linguistic cues that gesture toward something presumed to be shared, present, or self-evident. These include:

Exophoric deixis: pointing to something external to the discourse—“Look at that,” “Here we go,” “Now is the time.”

Endophoric deixis: referring within the discourse—“This shows that…,” “Such behavior is unacceptable.”

Typophoric deixis (as introduced in this model): referring not to physical or textual elements, but to presumed moral, metaphysical, or theological types—e.g., “justice,” “love,” “progress”—when used without grounding in divine ontology.

A single sentence may combine all three:

“We all know this is the right thing to do now—in the name of justice.”

But beneath this seamless formulation lies a cascade of assumptions:

What is “this”? A covenantal act of obedience, or a consensus-approved policy?

What is “now”? A kairotic moment of divine moral urgency, or a media-engineered affective surge?

What does “justice” signify? Is it anchored in God's law, or recoded through ideological consensus?

These deictic expressions often function as semantic placeholders—infused with emotional weight but emptied of ontological precision. When invoked in this way, they create a pseudo-sacred aura around ideas that may, in fact, be typologically false. The danger lies not in the words themselves, but in their unstated referents—which, if left unexamined, substitute cultural consensus for divine definition.

Clarification: In this framework, typophora refers to gestures toward abstract categories presumed to carry moral or metaphysical weight. These can be either onto-typophoric (rightly pointing to covenantally grounded types revealed by God) or semiotic-typophoric (culturally constructed and rhetorically persuasive, but ontologically empty). Typophoric deixis, then, is the act of invoking a category—such as “justice,” “love,” or “progress”—whose status as a real type must be tested, not assumed. The danger arises when pseudo-types are invoked typophorically, imitating the moral grammar of truth while severed from divine referent.

This is not a call to attack systems indiscriminately, nor to withdraw from discourse altogether. It is a call to:

Only by confronting discourse drift at the deictic level—where assumed meaning replaces examined meaning—can we begin to restore moral and theological coherence in a manipulated linguistic field. To reclaim truth in a manipulated field is not just a matter of accuracy—it is a refusal to participate in the discursive imitation of God, where pseudo-types and pseudo-tokens masquerade as moral clarity.

The Overton Window is typically framed as a horizontal mechanism—a fluid threshold of public acceptability managed through rhetorical shifts, media saturation, and narrative framing. In this view, discourse becomes adaptive, strategic, and moment-bound—its success measured not by truth, but by traction. Yet such a model ignores the vertical axis: the anchoring of speech in ontological reality and moral accountability. When referential gestures (signs, symbols, or propositions) are unmoored from the truths they are meant to convey—when typophoric references to morally real, abstract goods are flattened or subverted—language itself is weaponized. What remains is not communication but control, not persuasion but pressure. Thus, the true danger of an untethered Overton Window is not merely ideological drift, but semiotic collapse: the loss of any stable reference point beyond the social moment. Any model that seeks to recover discursive coherence must attend to both axes—horizontal awareness and vertical anchoring—so that language may again serve truth rather than control. When referential gestures are unmoored from truth, language begins to perform the illusion of divine speech—pretending to name into being. The result is not dialogue but simulation, not signification but pseudo-instantiation. The vertical axis is not just a metaphor—it is a guardrail against human attempts to mimic God’s double prerogative: to define kinds and instantiate presence.

Before proceeding into the technical apparatus of covenantal discourse diagnostics, it is instructive to examine a real-world case where these theoretical dynamics manifest. The case of Substack—a publishing platform heralded as a beacon of free speech—reveals how Overton dynamics, typophoric manipulation, and ontological drift operate even in spaces of apparent dissent. What follows is a dual-layered analysis: a focused case study of Substack, followed by a broader critique of mass platforms as mechanisms of scalable but domesticated dissent. In addition to the below, further case studies are presented for download as pdf files: Historical Overton Analysis (key Reformation figures, Movements and Jesus Christ) and Contemporary Case Studies .

Substack presents itself as a haven for free thinkers—writers fleeing the constraints of legacy media and institutional censorship. It promises unfiltered communication, financial independence, and a direct relationship with readers. But under Overton analysis, it reveals itself as a discursive holding zone—not a space of true epistemic liberation, but of licensed deviation.

Substack becomes a stage for epistemic orphans—those who sense the lie, but cannot find the Word.

One popular Substack term is “cognitive sovereignty”—a reframing of “liberty of conscience.” But this new term removes the vertical axis. It retains freedom of thought, but severs obligation to truth as something revealed. What remains is autonomy dressed in moral gravitas.

Rather than being a radical space, Substack is a pressure release valve:

Substack is not unique. It is symptomatic. All major platforms function similarly: they commodify critique, reward performance, and displace moral anchoring. This leads us to the broader diagnosis: the problem is not Substack—it is the architecture of scalable speech in a desacralized world.

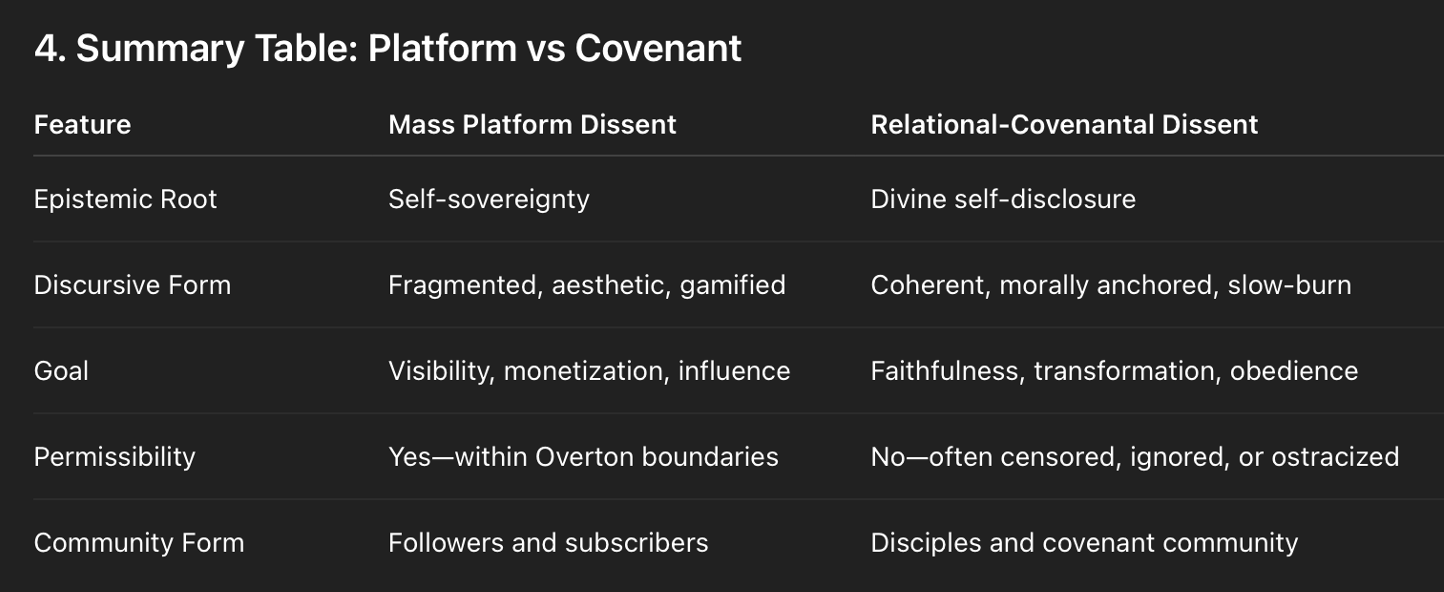

Modern digital platforms promise liberty of speech and access to diverse viewpoints. Yet beneath this appearance of plurality lies a tightly regulated ecosystem—an Overton-aligned simulacrum of dissent. What is offered is not liberty, but licensed variation—permissible deviation that feels radical, but remains structurally inert.

Mass platforms—Substack, Instagram, YouTube, Twitter (X), even newer alternatives like Rumble—serve not merely as hosts for content, but as meta-curators of consciousness. They regulate:

These constraints don’t silence speech; they reshape it into acceptable forms, ensuring the window of discourse remains wide enough to feel free, but narrow enough to prevent ontological disruption. Platforms don’t just limit what you can say—they preconfigure what you think is worth saying.

Many who sense the collapse of institutional truth migrate to such platforms, hoping to “speak freely.” They embrace concepts like cognitive sovereignty, radical transparency, or alternative epistemologies—yet without a relational anchor, their dissent remains abstract, self-referential, and ultimately recuperable by the system.

Without covenantal grounding, all critiques orbit autonomy. They rebel against the centre, but remain trapped in the circle.

The result is a ritual of resistance, not transformation. A new liturgy is enacted:

Authentic dissidence does not scale well, because it:

Such truth-telling is not “influential” but formational. It doesn’t build followings—it calls disciples. It is often misunderstood, censored, ignored, or regarded as extreme—not because it is wrong, but because it speaks from outside the system, not within its dialectic.

The voice crying in the wilderness is not the voice trending on the timeline.

The Overton Window is not merely a political mechanism—it is a semiotic filter of permitted perception. What is allowed to be seen, said, or morally endorsed is not neutral, but curated. Those who seek truth, therefore, must develop the capacity to:

Where truth cannot be scaled, it must be planted—not as megaphones, but as mustard seeds.

Discernment does not require institutional allegiance, but referential integrity. Those who learn to trace language back to its ontological root—who refuse to speak in borrowed types or manipulated symbols—will eventually be forced to confront the source of meaning itself. That encounter is not the end of analysis, but the beginning of understanding.

The Overton Window has shown how the public imagination is managed—not through overt coercion, but through the subtle erosion of moral language, typological clarity, and epistemic conscience. That analysis mapped the macro-discursive shift—how thresholds of the sayable, thinkable, and permissible are moved over time.

Yet to detect such drift in operation—within headlines, policies, sermons, and everyday language—requires more than conceptual awareness. It demands diagnostic precision. The question is not simply what narratives dominate, but how meaning is manufactured, reinforced, or suppressed at the level of words, signs, and context.

For this reason, the appendices that follow, after the Epilogue, offer two primary categories of analytical tools:

Micro-discursive tools, such as the Multidimensional Morpheme Analysis Tool (MMAT) and the Onto-Discursive Analysis (ODA). These expose meaning manipulation at the granular level—revealing how morphemes, tropes, implicatures, and typophoric gestures embed ontological simulation and frame moral response.

Metaphysical tools, such as the Onto-Epistemic Bandwidth Suppression Tool, which identifies how ontological category suppression narrows what may be known, said, or considered—functioning as a deeper logic beneath all discursive drift.

Unlike secular Critical Discourse Analysis, which often reveals power but cannot restore referential integrity, these tools are covenantally anchored. They treat language not as neutral exchange, but as moral action—subject to divine scrutiny, relational accountability, and ontological correspondence.

What follows in the appendices is not an afterthought but an extension: a set of instruments for those who would see through language to the moral architecture beneath, who would test words against the weight of being, and who would speak not with cleverness, but with fidelity.

📝 Endnote: Academic Touchpoint

While this framework is original in structure and theological in grounding, it engages themes explored in modern discourse theory. Concepts such as discursive constraint (Chomsky & Herman), framing and metaphor (Lakoff), and power/knowledge regimes (Foucault) are here reinterpreted through a biblical ontological lens—moving from critique to covenantal recovery. Unlike those models, which remain descriptive or deconstructive, this framework proposes typological reanchoring as both analysis and solution.

⚖️ Legal and Philosophical Disclaimer

This publication reflects theological and philosophical critique. All references to public figures (e.g., Snowden, Chomsky, Assange) are symbolic analyses of discursive roles, not allegations of intent or character. Interpretive claims should be read as analytical metaphors, not factual assertions. This is not political advice, legal commentary, or psychological evaluation.