In modern political discourse, systems of governance are typically evaluated based on surface characteristics: how power is distributed, how rights are articulated, or whether a system appears to maximize liberty, stability, or participation. Terms such as democracy, theocracy, republic, anarchy, and freedom of speech circulate with apparent clarity, yet they conceal profound conceptual ambiguity. What do these terms actually refer to? Do they name something ontologically real, or are they semiotic simulations—masks worn by systems that have long since severed their ties to truth?

This essay offers not merely a historical or political critique, but a deep ontological analysis. Rather than judging a government by outcomes or popularity, it asks a more fundamental question: Does this system preserve the moral structure necessary for an image-bearer of God to rightly respond to divine confrontation? If not, then no matter how democratic or efficient it appears, it fails at the level that matters most.

To do this, we must identify whether systems of governance correspond to true typological referents—God-ordained realities rooted in creation, covenant, and moral order—or whether they are typophoric distortions that mimic moral legitimacy while subverting it. This includes not only explicit tyranny but also the softer, subtler manipulations of modern liberal democracies, religious hierarchies, and ideological collectivisms.

The standard of evaluation is not cultural convention or philosophical tradition, but the ontological hierarchy embedded in God’s own revealed order, which may be summarized as:

God → Axiology (Value) → Deontology (Duty) → Modality (Right) → Law → Civic Procedure.

In this hierarchy:

This order stands in contrast to all self-centric systems, whether rights-based (libertarian), outcome-based (utilitarian), or proceduralist (liberal-democratic). These systems invert the hierarchy—placing human claims above divine confrontation—and thus become ontologically malformed.

This essay will proceed by:

The question, ultimately, is not what kind of government you prefer—but what kind of reality your system permits. Does it invite repentance? Does it protect conscience? Does it reflect the values of the kingdom? If not, it may be lawful—but it is not legitimate.

A system of government is not legitimate simply because it functions efficiently, provides order, or reflects the will of the majority. Legitimacy must be assessed ontologically: does the system uphold the moral structure that God embedded in creation and covenant? That structure is not arbitrary. It is revealed in the very nature of God and reflected in the relational obligations of human beings made in His image.

To evaluate this, we must first clarify the true nature of rights, and then situate those rights within the axiological–deontic–modal (ADM) framework that governs moral reality.

I.A. What Counts as a Right?

In this framework, a “right” is not merely a civil agreement or social utility. It is a relationally permitted moral action granted under divine order. For a claim to qualify as a true right, it must satisfy the following ontological and moral criteria:

Summary: A true right is not a standalone claim or societal preference. It must be embedded within the deeper structure of divine value, moral duty, and ontological legitimacy. Rights exist to protect moral agency in response to divine confrontation—not to license personal autonomy.

All legitimate rights emerge from a deeper structure: God → Axiology → Deontology → Modality

When this moral structure is reversed, systems begin to fracture ontologically:

These reversals are not just logically flawed—they are ontologically fraudulent, producing civic frameworks that simulate morality without preserving it.

Among all possible rights, the right to property provides the clearest test of whether a system respects the ADM order:

The legitimacy of a government does not rest on consent, tradition, or outcome. It rests on whether it acknowledges God’s axiological supremacy, enforces duties that reflect that order, and permits rights that are genuinely grounded in that moral frame.

The systems we will evaluate in this essay are not tested by how fair they seem—but by how faithfully they reflect this ontological sequence.

In assessing all political systems, it is not enough to critique what fails; we must also ask, what kind of governance did God originally intend for His image-bearers? The clearest historical manifestation of divine intent prior to distortion is the period of pre-monarchic Israel—a decentralised, covenantal society ruled not by kings, but by moral accountability to God and by the distributed wisdom of judges, raised only when necessary.

This was not anarchy in the modern sense. It was a theonomy—a social structure grounded in the revealed will of God, where no human authority mediated between conscience and divine law unless disorder made it necessary.

The period described in the book of Judges offers a key typological model:

The people were expected to self-govern under divine law, and only when disputes or violations arose did civil judgment occur. This reflects a radically different vision from both top-down absolutism and modern procedural democracies. Here, moral order preceded civic enforcement, and the burden of righteousness was placed on every individual and household.

“In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did what was right in his own eyes.” — Judges 17:6

This often-quoted verse is not an endorsement of relativism, but a lamentation of moral collapse when the relational tether to God’s law was severed. The system itself was not flawed—it was abandoned.

Rather than legislation by majority or executive decree, Israel’s law was already given—the Ten Commandments and covenantal statutes provided the shared framework.

These were not simply religious ideals—they were structural civic ethics, encoded in the community as a safeguard against tyranny, generational oppression, and institutional idolatry.

The Jubilee year (every 50 years) ensured that:

This was not utopianism—it was an ontological safeguard. The land belonged to God (Lev 25:23), and no permanent transfer of stewardship could take place. This prevented the creation of oligarchies and concentrated power structures that would subvert relational accountability and replace divine trust with human dominance.

Jubilee exposes the fallacy of both libertarian property absolutism and statist redistributionism. It affirms that ownership is neither sovereign nor collective—but relationally entrusted.

When Israel eventually demanded a king “like the nations,” it marked a rejection not of civic disorder, but of God’s direct rule (1 Samuel 8:7). The people preferred symbolic power and visible control over moral accountability.

God permitted Saul to be appointed, not as an endorsement, but as a concession to typological desire—a mirror of humanity’s craving for mediated legitimacy. The result was predictable: corruption, militarization, taxation, and divine silence.

Typologically, Saul represents pseudo-stewardship—human authority claiming to stand in for God, but lacking His alignment or humility.

In contrast, the New Testament reveals Christ not only as redeemer but as the perfect steward-king:

Christ embodies the kind of authority that Israel rejected: ontological humility, servant kingship, and alignment with the Father’s will. In Him, distributed relational theonomy is fulfilled—not abolished.

The Judges-era model, far from being archaic, was a typological preview of the moral structure God intended all governance to reflect:

This apostolic template is not a call to recreate ancient Israel—it is an invitation to recover the ontological principles that preceded, undergirded, and outlasted it.

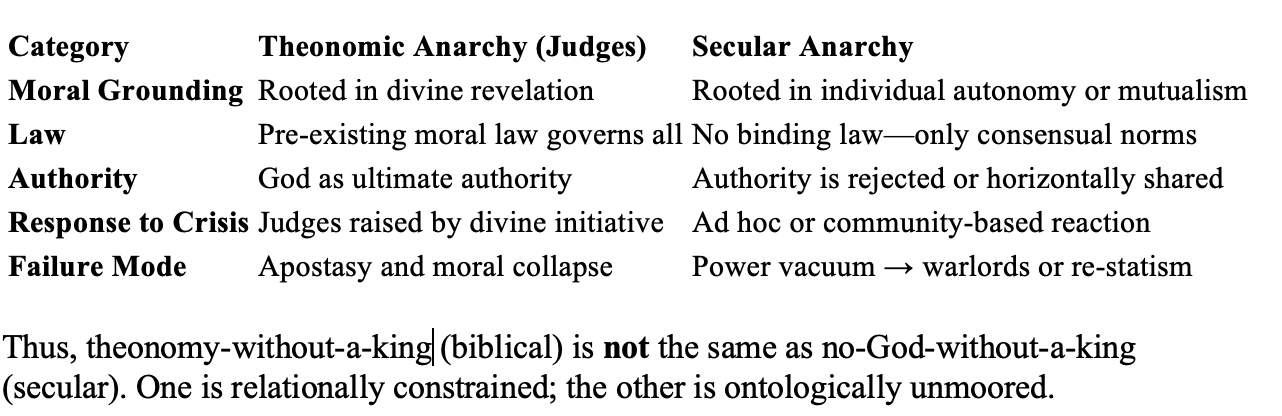

Secular anarchy, often romanticised as the purest form of liberty, is fundamentally unstable. While it may reject state coercion and hierarchical oppression, it does so without offering any coherent ontological grounding for order, rights, or relational stewardship. Without a revealed moral reference point, it collapses inward—either into tribal fragmentation or an eventual re-centralisation under emergent power.

Secular anarchism is not defined merely by the absence of rulers, but by the absence of moral grounding capable of constraining human will. Its vision of liberty is unanchored, its version of peace is probabilistic, and its concept of order is procedural rather than ontological.

Before proceeding, it is essential to clarify that anarchy in the biblical context (Judges-era theonomy) is not the same as secular anarchism.

Secular anarchist experiments have emerged sporadically in history—often during revolutions or state collapses:

Each of these illustrates the core fragility of secular anarchy:

The central flaw in secular anarchy is not procedural but ontological:

This leads to what we might call pseudo-stewardship without archetype: individuals or communities acting as if they are morally sovereign, without an external referent to justify their claims. Over time, such systems often:

Secular anarchists often claim their model is “value-neutral,” prioritising:

However, these principles themselves assume:

Without ontology, these principles become empty forms—subject to manipulation, inconsistent application, or rapid erosion under strain.

A society that disavows moral obligation but retains procedural habits is living on borrowed capital—ethically, ontologically, and spiritually.

In practice, secular anarchy often becomes the midwife of totalitarianism. Once the moral infrastructure collapses and the power vacuum deepens:

Eventually, one faction fills the vacuum and re-establishes order through raw power, not moral legitimacy. This pattern mirrors the historical arc of Israel:

The modern secular version plays out the same, but without divine intervention.

The period of the Judges represents a divinely sanctioned form of decentralized governance—a kind of covenantal republicanism. God Himself established this mode of self-rule, with no standing king or state apparatus, because under His moral order, external coercion was unnecessary when internal moral alignment prevailed. Governance was rooted not in institutional control but in the collective obedience to divine law and the personal responsibility of each tribal unit.

Though the tribes of Israel were territorially and administratively autonomous, their unity and peace endured so long as they submitted to the revealed will of God. Joshua’s leadership offered transitional cohesion, but once he passed, the people were expected to operate under divine law without a central human figure. This was not anarchy, but a distributed moral republic, wherein divine axiology replaced the need for coercive statecraft.

However, as covenant memory faded, a spiritual erosion set in. The book of Judges records repeated cycles of rebellion, oppression, repentance, and temporary restoration. The phrase “every man did what was right in his own eyes” (Judges 21:25) reveals not libertarian autonomy but axiological collapse—a refusal to retain God as the grounding of moral authority.

The decentralization model remained structurally intact, but its ontological underpinning disintegrated. Without alignment to divine law, self-governance devolved into factionalism, idolatry, and civil war. Even the judges themselves began to embody the spiritual degeneration of the people—culminating in Samson’s chaotic moral example and the eventual demand for a king in 1 Samuel 8.

III.F.iii. Typological Significance: Republicanism Under God’s Law

Despite its failure in practice, the Judges model remains a valid type of godly governance: decentralized, non-statist, and morally accountable to God alone. Its collapse is not a condemnation of decentralization, but of spiritual drift. It shows that liberty without ontology becomes rebellion—and that true republicanism is only sustainable when grounded in reverent moral order.

The governance structure during the Judges was not a concession to chaos but an expression of God’s original intention: that individuals would live under His revealed moral order through conscience, not coercion. It was not merely institutional minimalism, but a test of internal alignment. God did not desire external control—whether by monarchy, priesthood, or communal enforcement—but voluntary fidelity. The law was a moral mirror, not a civic harness. The failure of Israel was not due to a lack of institutional structure, but to the rejection of charity, humility, and disinterested benevolence as guiding principles. The covenant presumes that love of God and neighbour would govern conduct more effectively than law imposed from without.

Secular anarchy is not sustainable—not because humans cannot govern without a state, but because humans cannot govern without ontology. In the absence of God, every liberty becomes a contested construct, every right becomes a projection, and every attempt at justice becomes a simulation. Thus, even the most idealistic secular anarchism is a rehearsal for collapse, unless grounded in a relational ontology that precedes it.

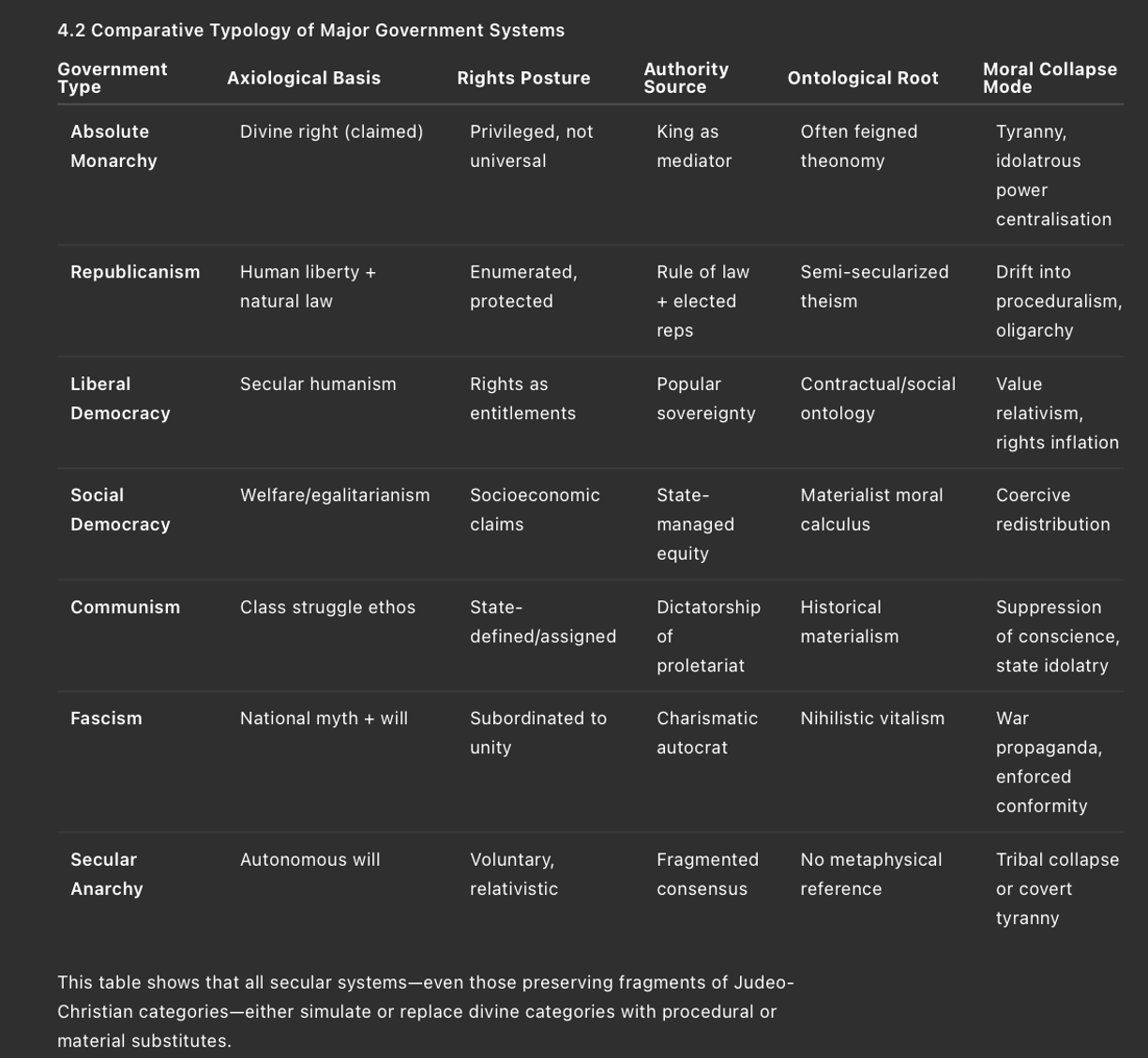

This section maps the prevailing human governmental systems—monarchical, republican, democratic, totalitarian, anarchic, and hybrid forms—showing their structural claims and ontological deficits. It applies a deep typological analysis to distinguish their moral foundations, their treatment of rights and duties, and their deviation from or distortion of divine governance.

Each system will be assessed according to the following criteria, grounded in the biblical model:

A common heuristic views government types on a left–right control spectrum:

However, this axis obscures a more critical dimension:

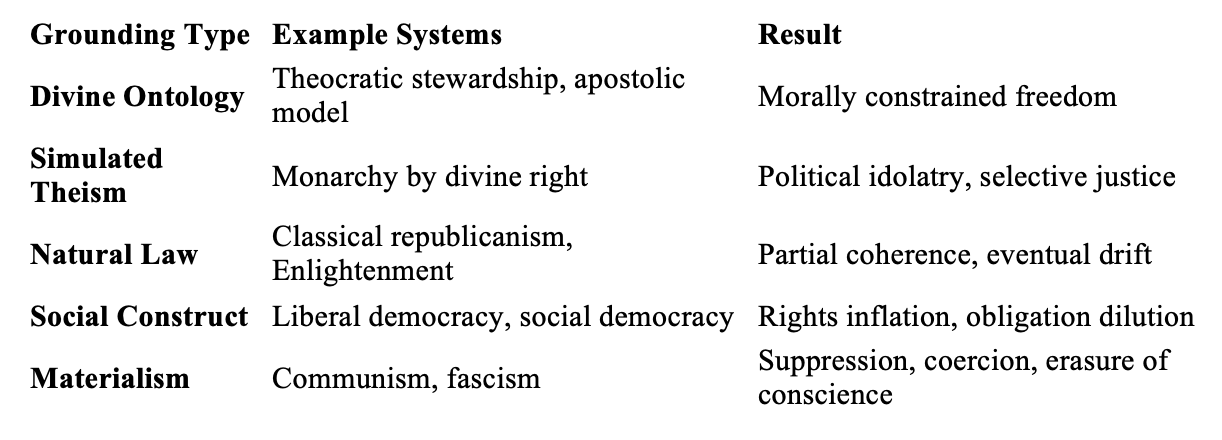

Moral Grounding Spectrum — What is the ontological source of law, rights, and governance?

All human systems, therefore, either:

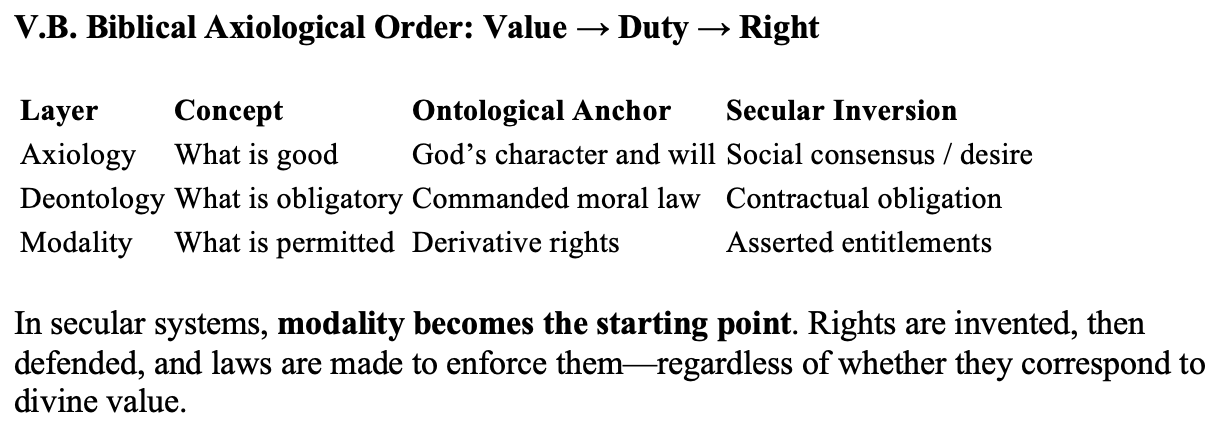

This section evaluates how different worldviews structure the relationship between rights, law, and morality, revealing the implicit ontological claims each framework makes. It clarifies the inversion between secular and biblical systems: whether rights precede law or emerge from duty, and whether morality is derived or discovered.

In secular models, rights are viewed as primary. They are:

This reverses the biblical hierarchy by making the human subject the arbiter of value.

In the biblical model, duties come first:

Therefore, rights are not asserted but inferred from moral order.

Example: The right to property exists not because we claim it, but because the command “You shall not steal” implies others have property that must be respected.

Law is not just a procedural mechanism to resolve conflict, but a moral architecture expressing:

In biblical terms, the law reveals:

The secular state cannot replicate this depth. It legislates only what is enforceable or consensual—not what is truly good.

Natural Law (discussed in more detail in Moral Taxonomy Essay ) seeks to derive universal moral rules through reason. It overlaps with divine law at points (e.g., murder is wrong), but lacks:

Divine Law reveals duties not just to neighbour, but to God. It includes:

Thus, divine law is covenantal, relational, and redemptive—not merely rational or utilitarian.

The modern obsession with rights becomes self-collapsing:

Without objective value, rights become:

This section clarifies the biblical model of separation between ecclesial and civic functions—not as a secular political convenience, but as an ontologically grounded division of responsibilities. It critiques the conflation of roles in both ecclesiocracy and statist theocracy while affirming the distinct, limited, and morally accountable roles of both institutions under God’s sovereignty.

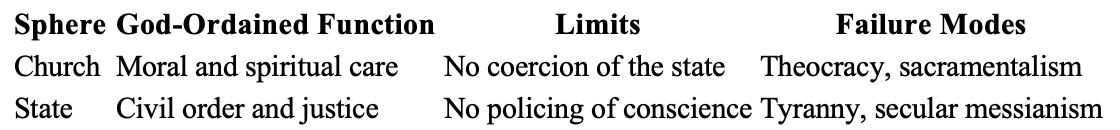

The idea of separation of church and state is not rooted in Enlightenment secularism, but in the biblical pattern of:

God’s law restrains both state and church, not one from the other, but each to its ordained function.

Examples:

At the heart of this separation lies the divine principle of liberty of conscience:

This principle predates modern human rights theory and undergirds:

True religious liberty arises not from civic tolerance but from divine restraint on institutional overreach.

The apostolic model of church governance preserved a strict ontological distinction between the ecclesia and the state. It recognized that the church’s authority was moral, spiritual, and typological, not coercive or territorial. The early church did not seek to govern civil affairs but to model a regenerate moral order, rooted in discipleship, relational accountability, and submission to Christ’s revealed will. This model upheld liberty of conscience not as a state concession, but as a divine prerogative stemming from the moral nature of truth itself.

By contrast, the Roman Catholic system represents a fundamental inversion of this order. Under canon law and the imperial-papal paradigm that developed after Constantine, the institutional church became a political body, claiming juridical authority over both individuals and nations. The Vatican, as a geopolitical entity, asserted ownership of lands, power over kings, and custodianship of salvation—effectively merging ontology, authority, and administration into a human-managed theocracy.

This is not a legitimate theocracy but a typological distortion: a simulacrum of divine governance, wherein the church arrogates to itself the prerogatives of Christ. Rather than stewarding moral invitation, it imposed sacramental compulsion. Rather than proclaiming truth unto voluntary repentance, it enforced conformity through inquisitions, anathemas, and civil sanctions.

This model obliterated liberty of conscience by collapsing the distinction between divine truth and ecclesiastical institution. It presumed the church could administrate spiritual access in a monopolistic and territorial sense—effectively denying the relational and ontological foundations of faith.

In contrast, the apostolic model preserved:

Thus, the difference is not merely historical or denominational—it is ontological and moral. The Roman model replaces divine moral authority with institutional control, whereas the apostolic model preserves God’s prerogative to govern souls through truth, not human coercion.

The Reformation recovered critical elements of biblical ontology:

However, most Protestant systems failed to fully separate ecclesial power from civic force:

While liberty of conscience was affirmed in theory, many reformers—pressed by political alliances—retained state-backed confessionalism. The result was an ambiguous model: spiritually liberated, but structurally compromised.

Apostolic decentralization, by contrast, exhibits:

When either oversteps:

Only by returning to the ontological structure of delegation—God → conscience → relational duty—can a just society preserve true liberty.

This framework clarifies that separation is not hostility, but sacred constraint. Each domain exists under divine sovereignty and is accountable to its ontological remit, not to each other’s overreach. That is the true meaning of biblical liberty.

This section demonstrates what happens when political or legal frameworks invert the ontological order—placing asserted rights above revealed value. Such inversion leads to systemic absurdities, inflated entitlements, and eventual moral collapse. A reductio ad absurdum structure is used to illustrate how secular logic, when detached from ontological reality, undermines itself.

In the correct order:

In the secular reversal:

This reversal is not only illogical—it is ontologically unstable.

These demonstrate how rights, once divorced from ontological limits, escalate into contradictions.

Property rights offer a unique window into the deeper ordering of value, duty, and liberty:

Under distorted frameworks:

When property rights are denied, diluted, or redefined by the state:

This reversal also results in pseudo-rights:

Typophoric dislocation occurs when claimed rights reference false typologies—imposing fraudulent categories into moral discourse.

Overview:This section evaluates the moral and ontological legitimacy of various governing systems based on their structural distribution of authority. It argues that hierarchical concentration of power—whether political, ecclesial, or economic—is incompatible with the covenantal order of divine governance, which instead affirms decentralized responsibility, mutual accountability, and liberty of conscience.

Despite their apparent ideological differences, syndicalism, communism, and capitalism all result in concentrated economic and social control:

Syndicalism centralizes ownership within trade unions or collective syndicates, substituting individual stewardship with oligarchic oversight.

Communism dissolves private property altogether, reassigning ownership to the state or a ruling class in the name of equality.

Capitalism, although affirming private property, often results in practical concentration of ownership in the hands of a few capital holders, enabling coercive economic influence over those with less.

➡ Shared trait: All three remove the locus of moral and material responsibility from the individual, placing it in a mediating hierarchy.

Church systems like Roman Catholicism, Anglicanism, and many forms of Reformed ecclesiology mimic secular governmental structures:

They maintain top-down control through sacerdotalism, apostolic succession, or synodical regulation.

Even well-intentioned reforms often preserve hierarchical centralization under a different name.

➡ These forms of ecclesial governance are structurally analogous to statist systems, violating the ontological pattern of voluntary moral governance under Christ as revealed in the apostolic model.

Scriptural governance structures—including the period of the Judges and the apostolic era—prioritize:

Self-government under divine moral law

Accountability to God directly, not to institutional intermediaries

Local judgment and redress, not centralized bureaucracy

Even where hierarchy exists (e.g., under Moses or Joshua), it is:

Temporary

Covenantal, not institutional

Accountable directly to God, not self-perpetuating

Wherever governance:

Concentrates power

Disconnects moral responsibility from the individual

Establishes tiers of access to truth, law, or justice

…it fails the ontological test. It replaces relational fidelity with structural dependency and undermines liberty of conscience.

➡ True governance serves as redress, not regulation. It arises when moral failure needs arbitration—not as a preemptive mechanism for control.

A table illustrating the critical differences between the models alluded to is presented below.

Not all hierarchy is ontologically corrupt. In heaven, hierarchy is real—but it is defined by moral posture, not power. Heavenly hierarchy reflects God’s own axiological character: it is grounded in truth, love, and justice; it operates through service and stewardship rather than domination. As Christ taught, “Whoever would be first among you must be servant of all” (Mark 9:35). This order does not coerce conscience, but appeals to it; its authority is transparent because it derives from moral alignment with God’s will. Resources are distributed as trust, not possessed as entitlement—stewardship replaces ownership. Christ exemplifies this heavenly order: He “humbled Himself” (Phil. 2:5–11), embracing the lowest place to fulfil the highest calling. In contrast, fallen human hierarchy is rooted in autonomy and the desire to rule. It justifies itself through birthright, strength, or constructed merit, and seeks control and prestige through coercion, whether legal, ideological, or structural. Earthly hierarchies conceal their self-serving aims beneath the veneer of order or justice, and appropriate resources not to bless but to secure power. This is the architecture of Babel and empire: the exaltation of the few, the suppression of conscience, and the centralization of what was meant to be shared.

When rights precede duty, and duty is divorced from truth, the entire civic edifice becomes unanchored performance.

This reinstates: (i) Duty as the context for liberty; (ii) Liberty as constrained by love and truth; (iii) Law as the guardian of justice, not the engine of self-definition.

God’s final vision is not the perfection of external systems, but the restoration of inward moral architecture. His Kingdom is not built on centralized oversight—even of the benevolent kind—but on the diffusion of moral agency across every person, renewed in His image. The highest principles are not efficiency or equity, but disinterested love, holy charity, and voluntary righteousness. “They shall all be taught of God” (Isa. 54:13), because His Spirit writes the law of love on the heart (Jer. 31:33). In this restored order, every soul governs itself under God, and does so not out of fear or social pressure, but from the overflowing abundance of grace, gratitude, and relational fidelity. This is the only government that cannot be shaken.

Yet this divine reordering of moral categories stands in sharp contrast to the logic often invoked during moments of public upheaval and institutional stress. In such moments, appeals to the “greater good” become dominant—but the foundation of that good, and the authority to define it, are rarely examined. This sets the stage for a deeper ontological discernment.

In modern governance and media discourse, the phrase “the greater good” is frequently invoked during times of societal stress—whether medical, military, environmental, or economic. These crises—such as the Spanish Flu, world wars, and the COVID-19 pandemic—function as moral inflection points. While their origins are often disputed and their narratives contested, their practical impact is to compel decisions, surface allegiance, and reveal the moral posture of individuals and societies.

From an ontological standpoint, the primary concern is not whether a crisis is engineered or organic, but what it reveals—and how it is leveraged. Crises function either as divinely permitted confrontations or as anthropic manipulations. Both test the soul; but only one does so while respecting its freedom.

God’s crises confront; man’s crises coerce.

Biblically, crisis is never arbitrary. Whether in the days of Noah (Genesis 6), Elijah’s confrontation on Mount Carmel (1 Kings 18), or the eschatological separation of sheep and goats (Matthew 25), crisis functions to reveal character and expose posture. God’s crises do not manufacture consent; they confront rebellion with clarity and invitation.

In contrast, anthropically managed crises—often framed as emergencies—serve to enforce consensus, elevate managerial authority, and generate the appearance of moral legitimacy. They seek control, not conversion. The crisis becomes a pretext, and the appeal to the “greater good” a mechanism for narrative unification and behavioral compliance.

Modern regimes have mastered the use of crisis as a rhetorical and legal tool. Invoking the “greater good,” they bypass normal conscience-based processes of persuasion in favor of institutional mandates, emergency powers, and censorship. This inversion exploits the appearance of moral urgency while denying the ontological basis of true moral conviction.

Where Scripture asks, “Whom will you serve?” (Joshua 24:15), modern systems ask, “Will you comply?”

This subtle but critical shift repositions the moral center away from divine allegiance and toward institutional survival. Conscience is not invited; it is overridden.

Unlike anthropic systems, God does not seek submission through structural force. His acts of judgment—whether flood, fire, famine, or cross—never annul liberty. Rather, they expose pre-existing allegiance. They provoke decision but do not predetermine it. In each case, individuals retain agency: to repent or resist, to yield or harden.

Crucially, God’s “greater good” is not utilitarian. It does not balance costs and benefits or sacrifice the few for the many. It reflects disinterested benevolence: a love that acts not out of need or survival, but out of fidelity to truth. Even where divine judgment brings consequence, it is always in harmony with justice, not strategy.

The secular invocation of “greater good” often collapses into a programmatic moralism—a manufactured imperative that substitutes procedural alignment for actual righteousness. The test becomes: are you aligned with the group, the media, the mandate?

This counterfeit morality is not grounded in disinterested benevolence but in biased institutional self-preservation. It cannot allow dissent, because dissent threatens the illusion of moral consensus. Hence, it resorts to:

Threats rather than conviction

Suppression rather than persuasion

Compliance rather than conscience

The very markers of divine moral order—voluntary assent, transparent authority, and mutual accountability—are inverted.

In godless systems, the word “good” becomes a typophoric fraud: it gestures toward moral categories it no longer retains. Detached from divine ontology, the term becomes elastic—able to justify nearly any action, provided it is claimed to serve the collective.

Without a transcendent standard:

“Solidarity” becomes forced unanimity

“Justice” becomes ideological retribution

“Compassion” becomes technocratic programming

The less ontologically anchored a society becomes, the more aggressively it must simulate moral weight through spectacle, repetition, and suppression.

What separates divine confrontation from human coercion is not merely intention, but method. God never overrides conscience. He appeals to it—invites it—summons it. Even in judgment, His purpose is moral restoration, not behavioral conformity.

Liberty of conscience is therefore not a civic luxury, but a divine entitlement, inseparable from what it means to bear the image of God. Any appeal to the “greater good” that nullifies conscience—by fear, law, or manipulation—stands in ontological rebellion against God’s order.

The state may restrain evil, but it cannot define the good. Only the Creator can do that—and He does so by conviction, not compulsion.

Some may object: “But isn’t God also acting for the greater good—abolishing sin, restoring order, preserving the universe?” In a sense, yes—but not in the way secular ethics imagines.

God’s greater good is not a trade-off; it is a revelation of righteousness. It is grounded in His immutable justice and disinterested love. His interventions do not bypass moral agency, but uphold it. Even when judgment entails suffering, it is proportionate, just, and invites repentance.

By contrast, human systems pursue ends that justify the means, often sacrificing liberty, truth, or conscience for control. They may speak of “the common good,” but lack the moral architecture to define or preserve it. Their “good” is often convenience masked as virtue.

Thus:

God’s greater good preserves agency; human greater good suppresses it.

God confronts to liberate; man coerces to maintain order.

God acts out of holy love; man acts from survival, fear, or ambition.

Every crisis—regardless of origin—is a test of allegiance. It becomes a stage for discerning the source of authority, the mode of response, and the respect for conscience. God uses crisis to expose posture, not to enforce uniformity. His goal is fidelity, not conformity.

If a system cannot preserve liberty of conscience, it cannot claim to serve the greater good.

If it must simulate righteousness through coercion, it has already forfeited its claim to moral authority.

In the valley of decision (Joel 3:14), the test is not how well we conformed, but whether we freely aligned with truth. That is the only greater good that matters.

[Click here to see table in a new window]

Adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948, the UDHR was conceived as a moral charter for a post-war world. Its 30 articles blend negative prohibitions (e.g., bans on torture) with positive entitlements (e.g., housing, healthcare)—and they do so without citing any transcendent source of value or duty.

The table below refracts each article through an ontological lens, asking four questions:

What right is asserted? 2. What duty is implied? 3. What value is invoked (if any)? 4. Does the claim align with, partially echo, or depart from the axiological–deontic–modal order?

Even apart from that analysis, readers should note a structural tension inside the UDHR itself: the early negative rights require only non-interference, whereas the later positive rights demand coercive provision by third parties or the state. That internal shift foreshadows the ontological drift this section will expose.

Following the diagnostic criteria established in the preceding sections, particularly the analysis of legitimate rights (Section 1.1) and the ontological ordering of axiology → duty → right, we observe that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) presents a typology of asserted entitlements without ontological or axiological grounding.

While some individual articles appear noble or intuitive, the collection as a whole constitutes an assemblage of sociopolitical preferences—a taxonomy of moral assumptions dressed as universal truths. But these are neither derived from revealed authority nor tethered to any coherent metaphysical architecture.

The UDHR fails even its own internal coherence test: it asserts rights without defining their nature, basis, or limits, and without resolving tensions between competing claims. The document lacks any framework of ontology, axiology, or modal force—there is no 'is', no 'ought', and no binding 'must'.

The UDHR is best understood not as a universal moral charter, but as a secular mythology—a politically expedient document aiming to preserve peace and prevent atrocities by appealing to shared sentiments, not shared foundations.

It is, in ontological terms:

A normative wishlist, not a moral warrant.

A coordinated narrative, not a coherent framework.

Atheistic in grounding, not merely secular in application.

Thus, any modal force it carries is sociopolitical, not moral; enforceable by courts or consensus, but never by conscience rightly aligned to truth. It demands no allegiance beyond human agreement, and secures none beyond human power.

The very structure of the UDHR—its length, lack of hierarchy, and rhetorical tone—invites deeper critique not just in content but in architecture. It reveals what may be called proliferation without parsimony: the excess multiplication of moral claims absent any axiological clarity or ontological restraint.

In sound philosophical systems, parsimony is a hallmark of integrity. Ontological parsimony avoids needlessly multiplying types; epistemic parsimony restrains baseless inference. The UDHR, by contrast, presents rights as an ever-expanding ledger of assertions, with no boundary conditions or ordering principles.

A system with no ontological base must resort to exhaustive enumeration—because it lacks the coherence to distill.

Rather than demonstrating moral depth, the sheer number of asserted rights signals the absence of any operative value hierarchy. Each new right is introduced as equally valid, equally urgent, equally inviolable—but without any reference point by which to adjudicate between competing claims.

The multiplication of rights is not a sign of richness, but of moral confusion. The list becomes a substitute for meaning.

The UDHR claims to be universal, but in reality it enables functional selectivity—certain rights are elevated, others ignored, depending on sociopolitical context. Because the declaration provides no means to prioritize or mediate conflict, rights become rhetorical weapons rather than tools of justice.

This is a form of moral inflation: the more rights are printed, the less they are worth. Selectivity without principle becomes inevitable.

In the absence of divine ordering, the human attempt to codify rights results not in clarity but in polemic. The UDHR is best understood as a moral manifesto, not a metaphysical covenant. It appeals to consensus, not conscience; it is humanistic in tone but atheistic in structure, with no ontological ceiling and no axiological floor.

This completes the structural critique and prepares the reader to reapproach the question of rights with a renewed understanding: that rights are not first-order claims but second-order consequences—deriving their force only when rooted in divine axiology and ordered duty.

This final section draws together the ontological, theological, and political threads of the essay. It reframes all legitimate human governance as either approximating or distorting the divine model and asserts the kingdom of God as the only coherent and morally grounded system of authority. Rather than a call for theocracy in the institutional sense, it is a call for ontological submission, moral alignment, and a reordering of all human systems under divine truth.

God's rule is not merely top-down imposition, but the manifestation of perfect moral order:

Unlike secular theocracies or coercive religious systems, God's kingdom governs through:

When human governance reflects this order:

This can only occur when:

The apostolic era reflects this best—not as anarchic, but as self-governed through shared allegiance to divine moral order.

The UDHR’s proliferation of unfounded rights, analysed in Section 9, underscores why discernment is indispensable; without it, endless assertions masquerade as moral law. Every system—democratic, authoritarian, ecclesial—must be evaluated through:

Discernment is not political activism, but moral obligation: the capacity to see rightly and respond faithfully.

When rights become untethered from divine origin:

Only when rights are derived from God’s character, embedded in moral duty, and enacted through relational alignment, do they become:

The task is not to pick the best human system, but to:

Only in the kingdom of God is authority not a tool of fear, but a mirror of truth.