This essay is offered as a work of theological clarification rather than doctrinal revision. Its aim is not to relax moral seriousness, undermine judgment, or displace established Christian convictions, but to restore order among categories that Scripture itself keeps distinct. Where longstanding tensions have arisen—particularly around sin, intercession, probation, and judgment—this study proceeds by disaggregation rather than denial. Readers are invited to engage the argument as a diagnostic framework, testing whether its re-ordering resolves interpretive strain without loss of gravity or coherence.

This essay arises from a sustained attempt to resolve a set of dissonance-inducing tensions within the Adventist theological tradition—tensions most clearly felt in its engagement with eschatology, probation, and the close of intercession, particularly as articulated in the Spirit of Prophecy and The Great Controversy. Adventism is unusual among Christian traditions in that it does not leave these themes implicit or metaphorical. It names them directly. Yet precisely because they are named rather than avoided, unresolved structural ambiguities become difficult to ignore.

The dissonance that necessitates this inquiry does not arise in abstraction, but from the attempt to hold together a set of claims Scripture and the Spirit of Prophecy place side by side. The Great Controversy depicts the redeemed surrounding Christ as ordered according to nearness, devotion, and intensity of allegiance, rather than according to degrees of moral flawlessness; yet it also speaks of a people at the close of probation who stand without an intercessor. At the same time, the same framework affirms that moral intelligences prior to Lucifer’s rebellion possessed no explicit awareness of law as law and yet were unfallen. Conversely, after the millennial Sabbath—the eschatological rest corresponding to the final day of the cosmic creation week—Scripture does not describe moral perfection as having been newly achieved or completed. The millennium is not presented as remedial or developmental, but as rest, disclosure, and vindication.

If completed moral performance were the criterion distinguishing the final generation, these claims become incoherent: zeal would be morally irrelevant, pre-lapsarian innocence unintelligible, and the Sabbath-shaped character of the millennium distorted.

The unresolved question therefore presses with force: what, precisely, distinguishes those who stand at the close of probation—standing without an intercessor—from those who have walked the salvific path before them? The tension dissolves only if allegiance, rather than completed moral execution, is what Scripture and the Spirit of Prophecy consistently treat as determinative. The underlying tension is not uniquely Adventist; Scripture already contains it. Revelation 22:11 speaks to fixity—“let the just remain just, and the filthy remain filthy”—while in the parable of the soils, moral perfection is never invoked; what is disclosed instead is purity of orientation and responsiveness to authority. This is in stark contrast to the inhabitants of the often quoted ‘Hebrew Hall of Fame,’ moral agents whom scripture declares to be saved yet mostly known for their glaring moral failures.

The argument developed here is not that Adventism teaches error, but that it leaves certain foundational assumptions insufficiently interrogated. Chief among these is the operative definition of sin. When sin is functionally treated as exhaustively equivalent to “transgression of the law,” significant downstream consequences follow—especially in how intercession, judgment, and readiness are apprehended. These consequences of such compression are not merely theoretical; they shape lived piety, assurance, and moral psychology.

Scripture itself resists such compression. The law already distinguishes between sins committed in ignorance and sins committed “with a high hand” (Num. 15:27–31, KJV), attaching radically different consequences to each. Any account of sin that treats all failure as morally uniform has therefore already departed from Scripture’s own moral grammar.

Stated plainly: sin cannot be reduced without remainder to transgression, and, correspondingly, intercession cannot be reduced to pastoral support or remedial assistance in response. Neither Scripture nor the Spirit of Prophecy sustains such a narrow symmetry. Where these reductions are assumed, interpretive strain emerges.

Scripture itself robustly resists the equation of sin and transgression. Isaiah writes,

“I have blotted out, as a thick cloud, thy transgressions, and, as a cloud, thy sins” (Isa. 44:22, KJV).

The asymmetry in the text precludes equivalence. Sin and transgression are not interchangeable terms differing only rhetorically; they occupy distinct moral registers.

Scripture operates with a more differentiated moral grammar than is often acknowledged, distinguishing sin, transgression, iniquity, error, and ignorance as non-identical conditions rather than rhetorical variants. The law itself distinguishes failures committed “through ignorance,” providing specific sacrificial provision for such cases and thereby differentiating them from defiant violation (Lev. 4:2, 13, 22, 27, KJV); David speaks of iniquity as a formative condition antecedent to conscious acts—“in sin did my mother conceive me” (Ps. 51:5, KJV); and the psalmist elsewhere distinguishes sin, transgression, and iniquity as morally discrete realities rather than interchangeable terms (Ps. 32:1–5, KJV). Christ Himself prays for those who “know not what they do” (Luke 23:34, KJV), while indicting willful resistance—“ye will not come to me” (John 5:40, KJV)—and explicitly calibrates accountability according to knowledge received: “that servant, which knew his lord’s will… shall be beaten with many stripes; but he that knew not… with few” (Luke 12:47–48, KJV). This grammar is reflected narratively: Rahab’s morally irregular actions are not treated as covenantal transgression but sin, while Rachel’s retention of idols within the covenant household constitutes intentional premeditated defiance (Josh. 2; Gen. 31, KJV), termed transgression.

A simplified definition of sin as ‘transgression of the law’—useful in limited pedagogical contexts—cannot therefore be treated as universally exhaustive without distortion.

Intercession is the divinely appointed ministration in view of sin, but only insofar as sin itself is rightly understood. If sin is reduced to transgression alone, intercession is correspondingly reduced to moral remediation—grace applied to defect, assistance applied to weakness. Yet Christ’s own testimony in judgment resists this framing.

In Matthew 7, those rejected appeal to their religious performance; they are not commended for it. They are rejected on relational grounds:

“I never knew you” (Matt. 7:23, KJV).

Acceptance is not grounded in output, but in recognition. Likewise, the language of the new birth does not describe a performative or progressive condition, but a categorical one. One is either born again or not. The variable is not temporal achievement, but a binary ontological relocation.

This places relationship—and more precisely, allegiance—prior to performance.

Many Adventists will respond that salvation has always been understood as relational rather than performance-based. That claim is correct, but often under-examined. The tradition simultaneously affirms probation, the close of intercession, character development, final judgment, and a people who stand without an intercessor at the end of time. It affirms both continued moral development and settled standing. These commitments coexist, but their internal relationships are rarely clarified.

As a result, sin is frequently arrested at the level of transgression, while intercession is treated as the comprehensive remedy—encompassing grace, strength, transformation, and support. Yet many of these operations are not unique to believers. Christ Himself teaches that God “maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good” (Matt. 5:45, KJV). If these are intercessory acts, they cannot by themselves explain the distinction Scripture draws at judgment.

Those who wish to avoid reference to the Spirit of Prophecy encounter the same difficulty within Scripture alone. Revelation portrays a final fixity of moral orientation at the close of probation—“He that is just, let him be just still: and he which is filthy, let him be filthy still” (Rev. 22:11, KJV)—indicating that some decisive variable has closed. Yet Christ’s teaching consistently denies that this distinction is publicly discernible or grounded in visible performance. His parables insist that separation is deferred and opaque: the wheat and tares grow together until the harvest, and the net gathers both good and bad fish without immediate distinction (Matt. 13:24–30, 36–43; 47–50, KJV). Christ’s judgment warning reinforces the same principle—profession and activity, even acts done “in thy name,” do not securely discriminate, while relational knowledge does: “I never knew you” (Matt. 7:21–23, KJV).

This logic is made explicit in the case of the thief on the cross, who offers no record of obedience, restitution, or future sanctification, yet is assured, “Today shalt thou be with me in paradise”* (Luke 23:42–43, KJV). His case is decisive precisely because he explicitly acknowledges Christ as King, exhibits no performative sanctification, and is accepted prior to any moral repair or completed obedience. His allegiance and fealty is declared and accepted as sincere and genuine. Scripture therefore affirms both final fixity and present opacity. Something decisive has closed, yet it is not publicly legible, nor reducible to observable moral performance. The thief collapses every performance-based eschatology and stands as the clearest biblical illustration of allegiance fixed without moral completion.

The tensions addressed here are therefore not uniquely Adventist in origin, but Adventist in visibility. They arise wherever Scripture’s affirmation of final fixity is read through a flattened moral grammar that equates sin with transgression and intercession with remedial assistance. Once resolved, the resulting framework does not remain denominational. It retrofits across Christian theology wherever similar compressions of sin and intercession quietly operate, generating anxiety where Scripture itself offers coherence.

* A debate about the placement of the comma in this verse is outside the scope of this discussion.

At this point the pressure in the argument is unavoidable. If Scripture refuses to discriminate finally based on performance, yet still discriminates decisively, then the difference must lie elsewhere. What Scripture consistently assumes—but rarely names—is a jurisdictional boundary.

This jurisdictional distinction is not speculative. Christ Himself treats moral failure differently depending on posture. To some He says, “Neither do I condemn thee” (John 8:11); to others, “Ye will not come to me, that ye might have life” (John 5:40). The acts are not weighed in isolation; the will’s orientation determines the response.

Moral failure is not treated uniformly because it does not occur uniformly. Some failures occur prior to acknowledged authority; others occur within it. Scripture distinguishes between blindness and rebellion, ignorance and defiance, weakness and repudiation—not by minimizing wrongdoing, but by locating it relative to jurisdiction. To sin outside covenantal alignment is not the same moral event as to fail within it.

This distinction is already operative in Scripture’s moral grammar. Christ prays for Peter not that he would not fail, but that his faith would not fail. The issue is not transgression alone, but allegiance. Likewise, Christ’s judgment does not turn on works performed, but on whether the agent is known. These are jurisdictional determinations, not praxeological audits.

The failure to name this boundary—between pre-jurisdictional and post-jurisdictional moral posture—forces Scripture’s categories to collapse. Sin is flattened into transgression alone; intercession is flattened into remedial assistance alone; and the close of probation is misheard as moral completion rather than the fixation of allegiance.

Once this jurisdictional distinction is made explicit, the tensions dissolve. Intercession can have phases without contradiction. Growth can continue without jeopardy. Judgment can disclose without recalibrating. And standing without an intercessor no longer implies moral flawlessness but settled belonging.

The pre- and post-jurisdictional distinction has its origin in Eden. Prior to the Fall, humanity’s moral life was not probationary in the sense later required, because allegiance was unfractured and uncontested. Obedience was neither self-conscious nor secured through mediation; it flowed from unbroken relational alignment with God. The temptation in Eden was therefore not merely to commit a prohibited act, but to accept an alternate authority—to reinterpret reality, goodness, and life itself apart from God’s word (Gen. 3:1–6, KJV). The Fall marks the first jurisdictional defection: not simply moral failure, but a transfer of allegiance that rendered human moral agency unstable. From that point onward, sin assumes multiple forms—error, ignorance, iniquity, and transgression—precisely because humanity now lives under fractured authority. Intercession, probation, and judgment do not arise to repair finitude, but to address this jurisdictional breach. Eden therefore establishes the condition that all subsequent redemptive structures presuppose: moral development now occurs under contested allegiance, until that allegiance is finally fixed.

Once the jurisdictional boundary is made explicit, intercession must be reconsidered accordingly. Much contemporary discourse treats intercession primarily as pastoral ministration: grace applied to weakness, strength supplied to defect, support rendered in response to failure. While none of these are untrue, they are not primary. They presuppose a more fundamental operation.

The intercession that dominates Scripture at points of crisis is not therapeutic, but stabilising. Its concern is not moral improvement, but alignment. Christ does not intercede so that failure never occurs, but so that allegiance remains invariant and does not collapse moral stress or moral failure. His prayer for Peter is decisive:

“But I have prayed for thee, that thy faith fail not” (Luke 22:32, KJV).

Notably, Christ does not pray that Peter would not sin, nor that the consequences of sin would be removed. He prays that Peter’s faith would not fail. The distinction is decisive: intercession here preserves allegiance, not performance.

Peter’s denial is neither prevented nor excused. What is preserved is jurisdictional orientation. The intercession addresses the risk of defection, not the presence of imperfection. This is intercession as alignment maintenance, not pastoral repair.

When intercession is reduced to pastoral support alone, its purpose is mislocated. It becomes a response to moral inadequacy rather than a preservative against jurisdictional loss. This reduction forces intercession to carry explanatory weight it cannot sustain, particularly at the close of probation, where the question is no longer growth but stability.

Correspondingly, the solution Scripture offers at the jurisdictional level is not regeneration understood as moral renewal, but adoption understood as settled belonging. Regeneration speaks to transformation; adoption speaks to status and standing. The latter, not the former, addresses the problem of jurisdictional stability.

Paul is explicit:

“Ye have received the Spirit of adoption, whereby we cry, Abba, Father” (Rom. 8:15, KJV).

This distinction does not oppose regeneration to adoption. Regeneration names inward renewal; adoption names juridical standing. Scripture consistently treats the latter as the stabilising category under judgment, without requiring the exhaustion or completion of the former.

Adoption is not the culmination of growth; it is the establishment of relationship. It precedes maturity, training, and formation. An adopted child may be immature, incomplete, and untested, yet their belonging is not provisional. Their development occurs within security, not toward it.

This is why Scripture can speak coherently of a people who stand at the close of probation without an intercessor. What has been secured is not moral completion, but filial alignment. Jurisdiction no longer requires preservation because allegiance has been stabilised. Pastoral formation continues, but jurisdictional mediation has completed its task.

Where adoption and regeneration are collapsed, regeneration is burdened with securing standing, and intercession is burdened with producing perfection. Scripture assigns neither task to them.

Seen in this light, the logic resolves cleanly. Pre-jurisdictional moral posture requires confrontation and disclosure. Post-jurisdictional posture requires stabilisation. Intercession serves alignment, not therapy. Adoption secures belonging, not maturity. And the close of probation marks the end of instability, not the end of growth.

What Scripture forecloses is rebellion, not finitude. What it secures is allegiance, not arrival.

The distinction between allegiance and performance is not an abstract theological construction. It is embodied, decisively, in the life of Christ Himself. Scripture presents Christ not merely as one who performed righteousness flawlessly, but as one whose obedience was fundamentally jurisdictional—rooted in acknowledged authority rather than outcome.

This becomes unmistakable in Gethsemane.

Christ does not approach the cross in a posture of triumphant certainty or untroubled resolve. He trembles. He recoils. He prays that the cup might pass. The moment is not one of visible mastery, but of submission under pressure. Yet it is precisely here that His obedience is perfected—not by performance, but by alignment. Christ’s obedience in Gethsemane is therefore not exemplary because it is emotionally untroubled or morally triumphant, but because authority is acknowledged prior to action. Allegiance is settled before suffering is endured. The order matters.

“Not my will, but thine, be done” (Luke 22:42, KJV).

Nothing is achieved in that sentence. No work is completed. No suffering has yet occurred. What is settled is authority. The question answered is not whether Christ can endure, but whether He will submit. Allegiance precedes execution.

This is why Scripture can say that Christ “learned obedience”: “Though he were a Son, yet learned he obedience by the things which he suffered” (Heb. 5:8, KJV).

Obedience here is not the accumulation of correct acts, but the maintenance of filial orientation under extremity. Christ does not learn what to do; He manifests to whom He belongs.

To interpret Christ’s life primarily as a record of flawless performance is therefore to miss its governing logic. His obedience is perfect not because it is uninterrupted by strain, but because it is never displaced by autonomy. Even in distress, authority is acknowledged. Even in weakness, allegiance is intact.

This Christological pattern clarifies why Scripture consistently resists performance as the final discriminator. If Christ Himself is vindicated first at the level of allegiance— “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased (Matt. 3:17; 17:5, KJV)”—then the same order must govern those who are “in Christ.”

Standing is established by alignment, not by display. Performance follows, but it does not found belonging. Gethsemane reveals what judgment ultimately weighs: not the absence of struggle, but the refusal of rebellion.

This is why the close of probation cannot coherently be read as the achievement of moral invulnerability. Christ Himself was not invulnerable. What He was, without remainder, was aligned.

With the grammar of sin restored, the meaning of standing without an intercessor becomes clear. It describes a people whose jurisdictional alignment is no longer reversible, not a people who have transcended finitude or attained moral perfection. What has settled is allegiance, not development. Intercession ceases where its purpose has been fulfilled: if intercession serves to preserve allegiance under probation, then its close signals not abandonment but settlement. What ends is not divine involvement, but the possibility of jurisdictional defection. The moral agent no longer stands in jeopardy of changing allegiance.

This is why Revelation can declare, “He that is just, let him be just still: and he which is filthy, let him be filthy still” (Rev. 22:11, KJV). The text does not announce moral completion, but the closure of moral volatility. What ceases is not growth, but reversibility. Scripture forecloses rebellion, not finitude.

This framework also clarifies statements in The Great Controversy that prior to the fall moral intelligences did not know that there was a law. In this context, “law” does not denote ignorance of divine order or moral good, but the absence of any conceived alternative allegiance. Obedience was not rendered self-conscious because rebellion had not yet become imaginable; loyalty had not yet been contrasted.

The same clarification resolves the depiction of the redeemed surrounding Christ in a gradient ordered by zeal. What is honoured is not differential moral perfection, but allegiance exercised without reserve or regard for cost—even unto death. Proximity reflects intensity of fidelity, not the completion of sanctification. This is entirely consonant with Scripture: “Whosoever will save his life shall lose it: and whosoever will lose his life for my sake shall find it” (Matt. 16:25, KJV); “He that loveth his life shall lose it; and he that hateth his life in this world shall keep it unto life eternal” (John 12:25, KJV); and “they loved not their lives unto the death” (Rev. 12:11, KJV).

This also resolves the lingering question of what, if anything, distinguishes those who stand without an intercessor from those who have walked the salvific path before them. Salvifically, the answer is nothing. The same criterion applies without remainder. Allegiance is fixed prior to the close of probation, whether that fixation is followed by death and sleep, or by continued life. Scripture already declares that those whose probation has closed are settled. In this respect, the final generation is not more secure, more justified, or more aligned than any who have previously sealed their decision and rested in Christ.

What is unique is not their standing, but their experience. They alone remain alive after the close of probation, maintaining fixed allegiance through an interval of unknown duration—the time between the close of investigative judgment and the return of Christ, whose length is known only to the Father. Others closed probation and slept; they must close probation and remain. “Standing without an intercessor” therefore names a historical and experiential condition, not a superior salvific state. God’s criteria do not change at the end of time; history does.

Seen this way, the tensions that originally generated anxiety dissolve without dilution. Sin retains its seriousness without being rendered monolithic; judgment retains its finality without becoming arbitrary; intercession retains its necessity without being stretched into perpetuity. Sanctification remains lifelong and essential, but it is no longer burdened with the task of securing standing.

What Scripture consistently discloses is not a calculus of moral sufficiency, but a determination of allegiance. The decisive question is not whether enough has been achieved, but whether defection has occurred. Belonging is therefore established prior to completion, and performance is rendered expressive rather than constitutive.

Under this ordering, the close of probation marks a transition in moral condition—not from imperfection to perfection, but from volatility to stability. Growth continues, obedience remains meaningful, and judgment remains real; what is removed is the threat that moral development itself might undo belonging.

What has been argued here is not a relaxation of moral seriousness, nor a redefinition of judgment, but a restoration of order. Scripture consistently treats allegiance as prior to performance, jurisdiction as prior to evaluation, and belonging as prior to completion. When sin is allowed its full moral grammar, and intercession is understood as stabilising alignment rather than compensating for defect, the anxiety that has long accompanied eschatological reflection dissipates without loss of gravity. Standing without an intercessor is revealed not as the achievement of moral invulnerability, but as the fixation of allegiance—an end to volatility, not an end to growth. What is finally closed is not formation, but rebellion. What remains is obedience without terror, judgment without confusion, and communion without mediation.

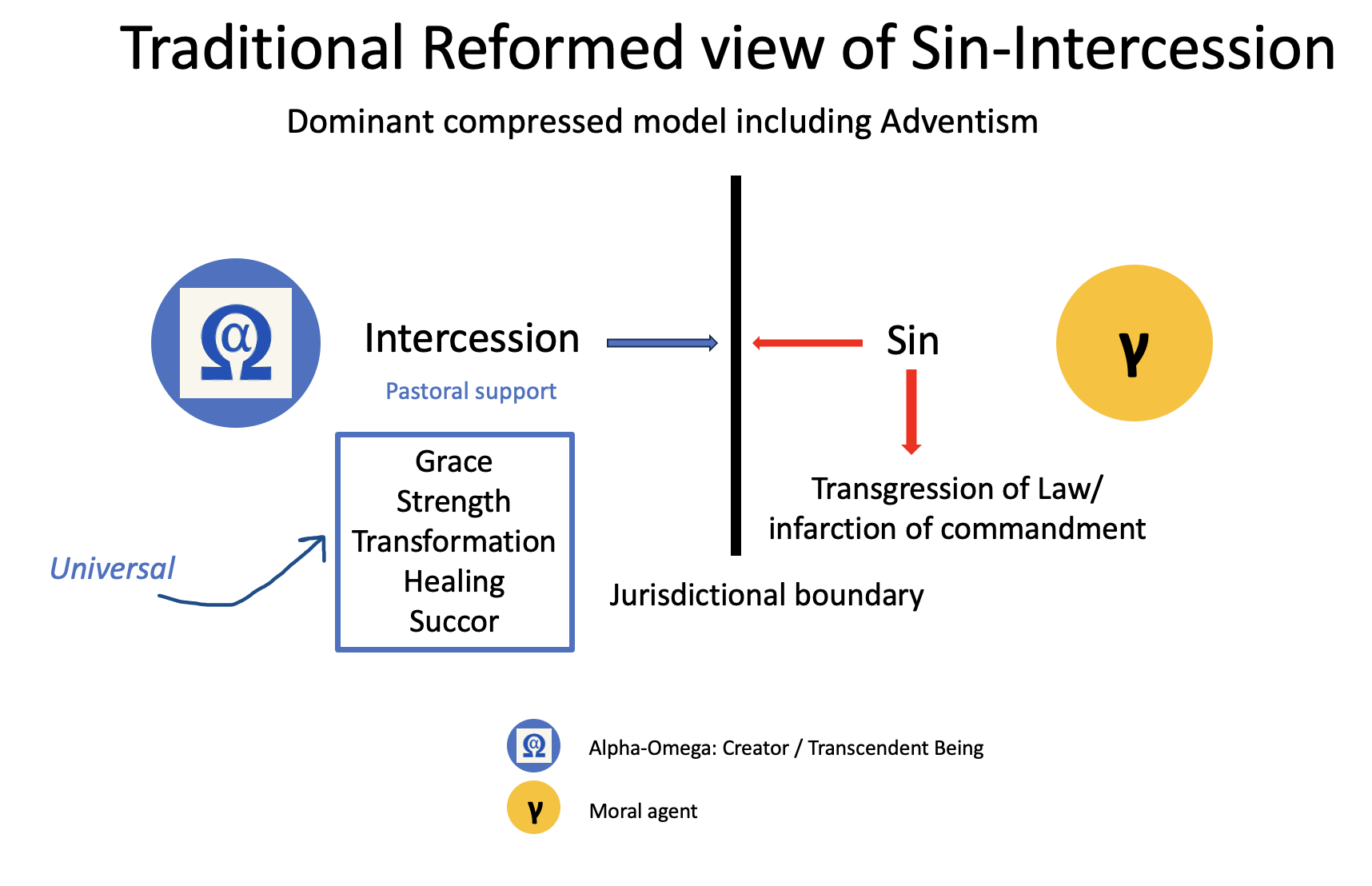

Legend – Compressed Sin–Intercession Model

This diagram represents the dominant compressed model of sin and intercession characteristic of traditional Reformed theology and commonly assumed within Adventism.

Sin is functionally identified with transgression of law, and intercession is correspondingly reduced to pastoral or remedial support addressing moral failure. Jurisdiction is treated as a static boundary rather than a dynamic category of allegiance, with justification and sanctification bearing the weight of standing.

This compression obscures upstream distinctions within sin itself and conflates jurisdictional alignment with formative moral processes, generating downstream tensions in eschatology, judgment, and the doctrine of the close of intercession.

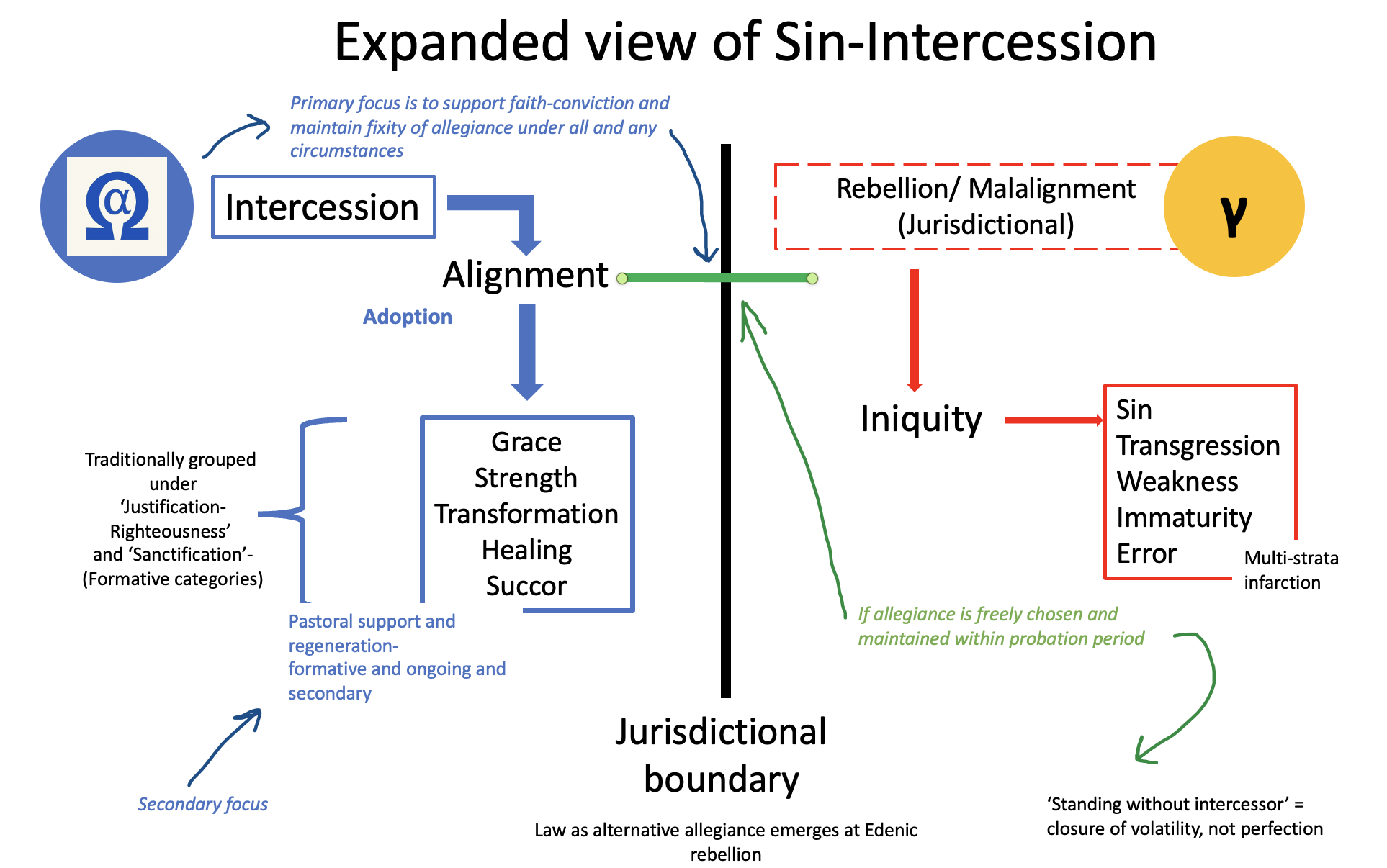

Legend – Expanded Jurisdictional Model

In this expanded model, intercession functions primarily to preserve and stabilise allegiance during probation.

Alignment (adoption) secures jurisdictional standing, while regeneration and sanctification remain formative and ongoing.

Sin is differentiated: iniquity names misalignment of allegiance, from which acts such as sin, transgression, weakness, immaturity, and error proceed. The close of intercession marks the end of moral volatility rather than the completion of moral formation.

Law, understood as an alternative allegiance, emerges only after rebellion.