Liberty of conscience is often confused with freedom of speech or freedom of religion. These are civic arrangements that regulate outward expression. Liberty of conscience belongs to a different order altogether.

It is not a political privilege, but a metaphysical necessity. It does not arise from social tolerance, psychological autonomy, or pluralistic restraint. It arises from reconciliation already accomplished. It is not neutral, and it is not optional. It is a necessary consequence of atonement completed (John 19:30; Hebrews 9:26–28; Hebrews 10:10–14; Romans 8:1).

In the Christian gospel, reconciliation is not proposed, negotiated, or conditionally extended. It is finished. The full cost of rebellion has been borne (Isaiah 53:5–6; 1 Peter 2:24). Judgment has been absorbed without remainder (Romans 8:3; 2 Corinthians 5:21). Nothing is held in reserve as leverage. Nothing awaits activation upon refusal. There is no outstanding penalty to be enforced (Hebrews 10:18).

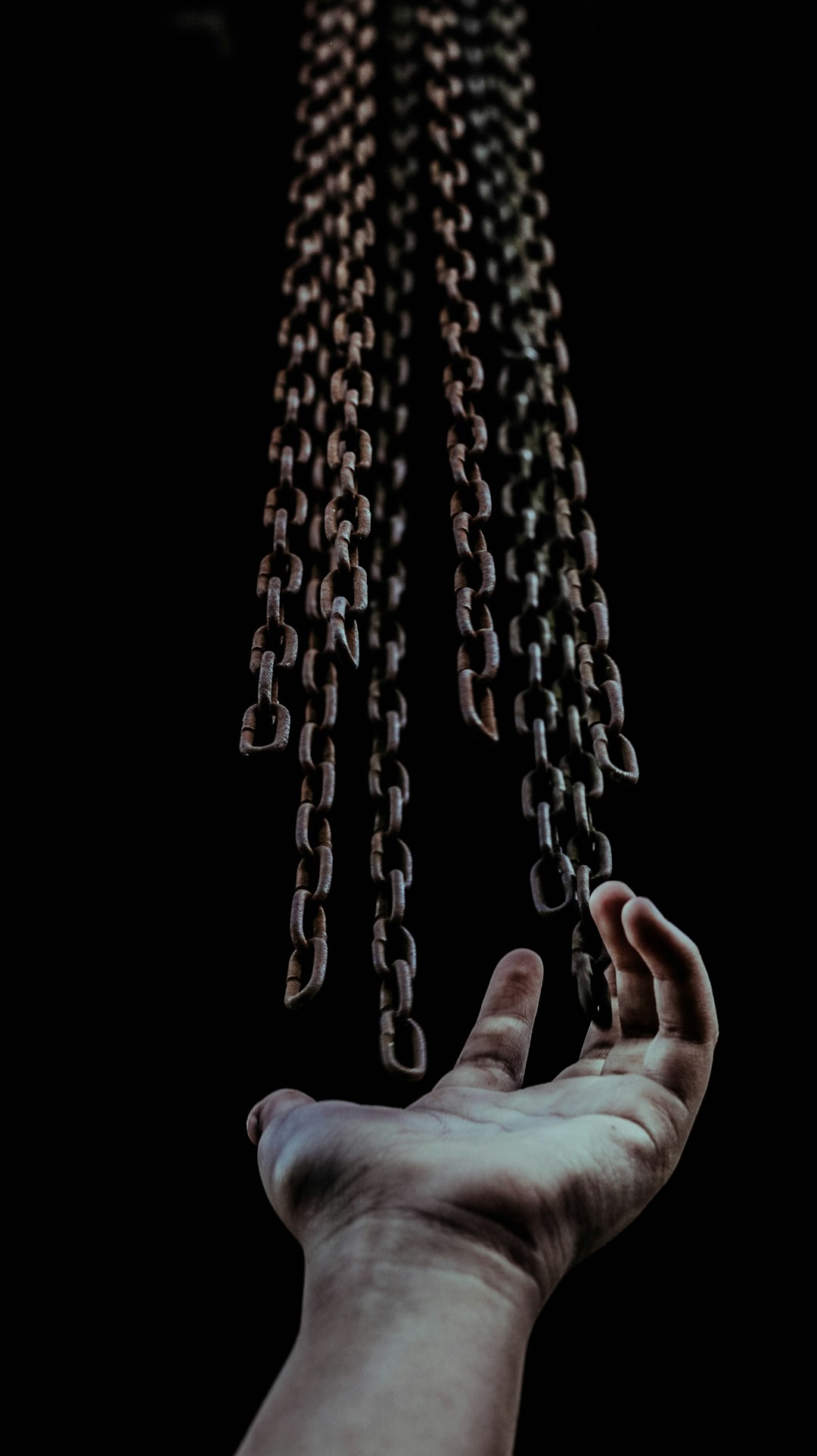

What must be made explicit at this point is the structural difference between consequence and coercion. The gospel does not eliminate consequence; it renders consequence non-instrumental. Under coercion, consequence is weaponized—used as leverage to extract inward assent through external cost. This is the grammar of “do this, or else.” But where reconciliation is complete, no such leverage remains available. What follows from refusal is not a threatened penalty imposed to force belief, but the boundary-condition of a reality declined (John 3:18–21; Luke 13:24–28). Participation cannot be compelled, because participation, by its nature, requires alignment (Matthew 16:24; John 15:4–6). Coercion therefore becomes not merely immoral, but ontologically incoherent.

To coerce belief is to behave as though reconciliation were still pending. It is to treat judgment as if it remained deployable. It is to deny, in structure rather than in speech, that atonement has been trusted to stand on its own (Galatians 2:21; Hebrews 10:29).

Liberty of conscience is therefore not permissive neutrality. It is not a suspension of judgment. It is the only moral condition consistent with judgment already borne. Where judgment remains incomplete, coercion becomes logically possible. Where judgment is complete, coercion becomes structurally impossible (John 12:47–48; Acts 17:30–31).

This is why conscience cannot be governed by threat. God does not multiply penalties to secure belief. He does not force participation. He does not compel assent (Matthew 23:37; John 6:66–68; Revelation 3:20). Faith emerges only where no leverage remains (Ephesians 2:8–9).

Refusal does not incur a secondary punishment. It does not activate latent sanction. It results only in non-participation in a life already offered (John 3:16–18; John 5:40). This is not permissiveness. It is metaphysical coherence.

Liberty of conscience is therefore not a concession to rebellion. It is the moral space created by reconciliation’s finality (Romans 5:1–2; Hebrews 4:16).

Any system that reintroduces coercive leverage—whether through law, institution, sacrament, culture, or threat—confesses, by its structure, that reconciliation has not been trusted to stand (Galatians 5:1; Colossians 2:20–23; Hebrews 10:14).

Liberty of conscience is often confused with freedom of speech or freedom of religion. These are civic arrangements that regulate outward expression. Liberty of conscience belongs to a different order altogether (Acts 5:29; Romans 14:4; James 4:12).

It is the probationary moral field in which every agent must respond to a reconciliation already accomplished. It is not neutrality, and it is not autonomy. It is accountable freedom, sustained only so long as probation endures (Deuteronomy 30:19; Joshua 24:15; Acts 17:30–31).

To describe conscience as “neutral” is already to distort it. Conscience is never a blank canvas. Every moral agent stands in a noetic posture that already bends either toward reverent alignment or autonomous suppression (Romans 1:18–21; John 3:19–21). Delay forms posture; non-response is itself response (Hebrews 2:3; Luke 19:41–44). What secular discourse presents as a zone of suspended judgment is in fact an ontologically charged arena in which allegiance is being disclosed (Matthew 12:30; John 8:42–47).

Liberty of conscience is therefore not permission to do evil, nor license to invent truth. It is the divinely granted space in which fidelity or rebellion may be revealed precisely because coercion has been rendered obsolete (Galatians 5:13; 1 Peter 2:16). Freedom here is not the absence of accountability but the condition that makes accountability meaningful (Romans 14:10–12; 2 Corinthians 5:10).

This liberty is time-bound. It is sustained by divine patience, not guaranteed by human right (Romans 2:4; 2 Peter 3:9). To mistake probation for permanence is to confuse mercy with license (Ecclesiastes 8:11; Jude 4). Liberty endures only while choice remains possible, and it terminates when posture becomes fixed (Hebrews 9:27; Luke 13:24–28). Judgment does not negate liberty; it vindicates it by showing that freedom was real (Romans 2:6–8; Revelation 20:12).

Liberty of Conscience The divinely granted, probationary, accountable freedom to align with or resist revealed truth in a context where no penalty remains to be leveraged (Deuteronomy 30:19; Matthew 23:37; John 6:66–68).

Freedom of Speech A civic protection of external expression. Valuable, but downstream from liberty of conscience and liable to distortion when detached from reconciliation (Proverbs 29:25; Isaiah 5:20).

Noetic Posture The inward stance of the moral agent—humility or autonomy—by which truth is received as invitation or resisted as confrontation (Psalm 51:6,17; John 7:17; Romans 8:7).

Coercion The use of threatened penalty or enforced consequence to secure inward assent, allegiance, or belief. Coercion targets conscience by external cost and presupposes an enforceable judgment (Daniel 3:4–6; Daniel 6:7–9; Revelation 13:15–17).

Liberty of conscience exists by divine permission, not by human invention. It belongs within the framework of the Divine Double Prerogative (DDP): God alone holds authority both to grant being (auctoritas essendi) and to determine what may be instantiated (auctoritas instantiandi) (Genesis 1:1; Psalm 24:1; Acts 17:24–28; Colossians 1:16–17).

This prerogative explains who grants liberty, but not why coercion is excluded. The exclusion of coercion arises not merely from sovereignty but from reconciliation accomplished. Divine prerogative establishes the field; atonement determines its non-coercive character (John 19:30; Hebrews 10:10–14; Romans 5:1–2).

Liberty is therefore neither absolute nor self-sustaining. It is bounded by probation and upheld only so long as God maintains the conditions of moral encounter (Acts 17:26–31; Romans 2:4–8). To imagine conscience as perpetual autonomy is to mistake divine patience for eternal license (Ecclesiastes 8:11; Jude 4). Liberty does not eliminate judgment; it is what renders judgment coherent (Hebrews 9:27; 2 Corinthians 5:10).

The architecture of liberty of conscience can be traced through the Axiological–Deontic–Modal framework:

Axiology (Value Orientation): Liberty reveals what the agent truly values when no force compels (Matthew 6:21; John 3:19–21; Romans 2:7–8).

Deontology (Duty Recognition): Obligation is perceived without enforcement; duty is encountered, not imposed (Micah 6:8; Romans 12:1–2; James 1:25).

Modality (Perceived Possibility): Posture shapes the field of possibility. Humility perceives invitation; autonomy perceives burden (Matthew 11:28–30; John 7:17; Romans 8:7).

Praxis (Manifest Action): Action discloses posture. Liberty makes allegiance visible (Matthew 7:16–20; John 15:4–8; James 2:17–18).

This structure operates within probation precisely because reconciliation has removed coercive leverage. Without liberty, moral agency would collapse into determinism or enforced compliance masquerading as obedience (Galatians 5:1; Romans 6:16–18).

Conscience does not generate truth; it meets disclosed reality. Knowledge here is relational first and propositional by disclosure. Posture governs reception, not existence (John 1:9; John 7:17; Romans 1:18–21; 1 Corinthians 2:14).

Once reconciliation is complete and conscience is free, the mode of relationship must change. The gospel does not merely alter obligations; it replaces the relational grammar by which obligation itself is understood (Jeremiah 31:31–34; Hebrews 8:6–13; Romans 7:4–6).

A contract secures compliance through enforceable penalty. Its stability depends on leverage, surveillance, and sanction (Exodus 21:7–11; Deuteronomy 28:15–68). A covenant, by contrast, rests on prior self-giving. Fidelity flows not from threat but from commitment already given (Genesis 15:1–18; Exodus 19:4–6; Ezekiel 16:8; Romans 5:8).

This distinction is not rhetorical. It is ontological.

Where reconciliation has been accomplished, relationship cannot remain contractual without contradiction (Romans 8:1–4; Galatians 4:4–7). A coerced covenant is a contradiction in terms. Enforcement does not preserve covenant; it negates it (2 Corinthians 3:6; Galatians 3:2–3).

Any system that:

• enforces belief,

• polices conscience, or

• punishes dissent,

has already abandoned covenantal grammar and reverted to contract (Daniel 3:4–6; Daniel 6:7–9; Revelation 13:15–17). This reversion does not merely reflect poor pastoral judgment or historical excess. It is a structural denial of reconciliation’s sufficiency. It confesses, in practice, that self-giving is no longer trusted to secure allegiance (Galatians 5:4; Colossians 2:20–23; Hebrews 10:29).

Covenant does not eliminate obedience. It eliminates extraction. Fidelity is no longer compelled; it is disclosed (John 14:15; John 15:9–10; 1 John 5:3). Where coercion appears, covenant has already been displaced (Matthew 23:4; 1 Peter 5:2–3).

From covenantal relationship flows a decisive anthropological consequence: faith is a matter of posture, not performance (Psalm 51:16–17; Isaiah 66:2; Luke 18:9–14).

Performance systems are necessarily coercive. They require:

• measurable outputs, • monitored behavior, • audited compliance (Matthew 23:23–28; Colossians 2:20–23).

Posture concerns orientation rather than output. It refers to the inward stance—humility or autonomy—by which truth is received or resisted (John 7:17; Romans 8:7; James 4:6). Performance belongs to contracts; posture belongs to covenants (Jeremiah 31:33; Hebrews 8:10).

When belief must be enforced, posture is displaced by metrics. External conformity substitutes for inward allegiance. Surveillance replaces trust. Fear replaces invitation (Galatians 4:8–11; Matthew 15:8–9).

This collapse is not incidental. It is inevitable.

Performance systems arise precisely where reconciliation is not trusted to do its work. They aim at what can be controlled because they cannot touch what matters. They evaluate appearance because posture remains inaccessible (John 2:24–25; Luke 16:15).

Scripture is explicit on this point: God does not evaluate faith by output. He looks not on appearance but on the heart (1 Samuel 16:7; Psalm 44:21; Jeremiah 17:10). Any system that reverses this order aims at what God does not even measure (Matthew 23:27; Luke 11:39–44).

Thus coercion does not strengthen obedience. It corrupts its meaning. It produces compliance without conviction, silence without assent, conformity without faith (Isaiah 29:13; 2 Timothy 3:5). What it secures is not allegiance but acquiescence (John 12:42–43).

Coercion is often condemned as immoral. That condemnation is insufficient. Coercion must be exposed as false.

Coercion is not defined by intensity but by function.

Coercion is the use of threatened penalty or enforced consequence to secure inward assent, allegiance, or belief (Daniel 3:4–6; Daniel 6:7–9; Revelation 13:15–17).

This includes:

• physical force, • legal penalty, • institutional exclusion tied to belief, • economic or vocational leverage, • sacramental denial used as pressure.

What unites these forms is not severity but leverage. Each attempts to produce inward alignment by external cost (Matthew 10:33; John 12:42–43; Galatians 2:11–14).

Coercion Presupposes Unfinished Judgment

Coercion only operates where:

• a penalty still stands, • judgment can still be applied, • fear can still be leveraged.

But where reconciliation is complete, none of these conditions obtain (John 19:30; Hebrews 10:10–14; Romans 8:1).

There is no remaining penalty to weaponize (Hebrews 10:18).

Therefore coercion is not merely excessive or cruel. It is ontologically incoherent. It behaves as though reconciliation were still pending and as though punishment remained a legitimate tool of persuasion (Galatians 2:21; Hebrews 6:6).

Any system that coerces conscience thereby confesses—structurally, even if not verbally—that reconciliation has not been trusted to stand on its own (Galatians 5:1–4; Colossians 2:20–23).

Coercion Cannot Reach Conscience

Conscience is not a switch. It cannot be compelled without being destroyed (Romans 2:14–15; Proverbs 4:23).

Coercion can produce:

• compliance, • silence, • conformity (Isaiah 29:13).

It cannot produce:

• conviction, • assent, • faith (John 6:66–68; John 12:42–43; Romans 10:10).

Which means coercion cannot achieve the very thing it claims to secure. It is instrumentally false. It substitutes fear for truth and appearance for allegiance (Matthew 23:27–28; 2 Timothy 3:5).

This is why Scripture treats coerced religion not as partial obedience but as abomination (Isaiah 1:11–15; Amos 5:21–24). What is coerced is not faith at all (Hebrews 11:6).

Coercion Reverts to Contract

Once covenant is understood as resting on prior self-giving, the category error becomes unavoidable (Genesis 15:1–18; Exodus 19:4–6; Romans 5:8).

Contracts require enforcement. Covenants presuppose commitment (Jeremiah 31:31–34; Hebrews 8:6–13).

Coercion belongs only to contracts (Deuteronomy 28:15–68).

Therefore any coerced religious system:

• has abandoned covenant, • reverted to contract, • and denied the relational grammar of redemption (Galatians 4:4–7; 2 Corinthians 3:6).

This is not a polemical charge. It is definitional.

Coercion Aims at the Wrong Object

Coercion targets externals because externals are controllable. But God evaluates posture, not performance (1 Samuel 16:7; Jeremiah 17:10).

Any system that monitors belief, audits compliance, or measures orthodoxy by output is aiming at what God does not even evaluate (Matthew 23:23–28; Luke 16:15). It is therefore theologically blind (John 2:24–25).

This diagnosis is not modern.

Christ refuses coercion outright. He allows disciples to walk away (John 6:66–68), rejects political power (Matthew 4:8–10), and rebukes violent defense (Matthew 26:52).

Apostolic authority explicitly forbids domination, not merely abuse (1 Peter 5:2–3; 2 Corinthians 1:24).

In Daniel and Revelation, false systems are marked not first by doctrinal error but by compelled allegiance and enforced worship (Daniel 3; Daniel 6; Revelation 13).

Coercion is not the solution Scripture offers. It is the sign Scripture condemns.

The logic is inescapable:

If reconciliation is complete, no penalty remains to be enforced (Hebrews 10:18; Romans 8:1).

Coercion requires an enforceable penalty (Daniel 3:6; Revelation 13:15).

Therefore coercion presupposes unfinished reconciliation (Galatians 2:21).

Any coercive religious system denies reconciliation by structure, not merely by speech.

Coercion is thus self-refuting within a Christian framework.

Historically and biblically, coercion yields:

• hypocrisy instead of holiness (Isaiah 29:13; Matthew 15:8), • rebellion instead of allegiance (Exodus 32; John 6:66), • collapse instead of unity (Matthew 23:38; Galatians 5:15).

This is not accidental. It is causal.

Truth compels only by being true (John 18:37). Anything else is spectacle, fear, or power—never faith (1 Corinthians 2:4–5).

The argument now stands complete:

Atonement accomplished → no remaining penalty (Hebrews 10:14) Liberty of conscience → no leverage possible (Galatians 5:1) Covenant, not contract → no enforcement mechanism (Jeremiah 31) Posture, not performance → no surveillance needed (1 Samuel 16:7)

Therefore → coercion is false, futile, and self-indicting.

Coercion is not merely rejected. It is rendered obsolete.

Once liberty of conscience is detached from completed reconciliation, coercion re-enters—not always overtly, but structurally. History’s major misframings of liberty do not reject freedom outright; they redefine it in ways that quietly restore leverage (Galatians 5:1; Colossians 2:20–23).

Modern political philosophy reframed liberty of conscience as a permanent individual right: the freedom to believe whatever one wishes indefinitely. This move severed liberty from divine prerogative and from eschatological accountability (Judges 21:25; Proverbs 14:12).

In doing so, it emptied liberty of weight. Freedom became preference. Conscience became private opinion. Accountability was displaced from God to consensus (Romans 1:21–25; Isaiah 5:20).

Ironically, this vacuum invites coercion back in through the state. Once liberty is no longer grounded in reconciliation, it must be managed—balanced against harm, regulated for cohesion, constrained for stability. What begins as neutrality ends in bureaucratic enforcement (1 Samuel 8:10–18; Ecclesiastes 5:8).

Post-Reformation Europe reframed liberty as toleration: a permission granted by magistrates to dissenters for the sake of civic peace. Conscience survived, but only precariously.

This model preserved order at the cost of ontology. Liberty became revocable. Belief survived by sufferance. Coercion remained structurally intact, merely postponed (Daniel 6:7–9; Esther 3:8–11).

Toleration is not liberty. It is the admission that coercion remains legitimate, merely delayed (Acts 4:18–20; Acts 5:29).

Modern psychology reduced conscience to conditioning, instinct, or socialization. Moral encounter was re-described as internalized pressure. Responsibility dissolved into mechanism (Romans 1:18–21; Jeremiah 17:9).

This reduction does not eliminate coercion; it naturalizes it. If conscience is merely conditioned response, then re-conditioning—through education, therapy, or narrative control—becomes morally acceptable (Isaiah 5:20; Colossians 2:8).

What cannot be denied ontologically will be manipulated therapeutically (2 Timothy 4:3–4).

A further distortion assumes that majority opinion secures liberty. Scripture and history testify otherwise. The many aligned against Noah (Genesis 6:5–7), against the prophets (1 Kings 18:22; Jeremiah 7:25–26), and against Christ Himself (Matthew 27:20–23).

Majorities do not restrain coercion; they amplify it. Consensus provides cover, not correction (Exodus 23:2). Liberty of conscience has never been safeguarded by numbers, but only by accountability to God (Psalm 118:8–9; Proverbs 29:25).

Across these misframings, the pattern is consistent: liberty is detached from reconciliation, and coercion returns under another name (Galatians 5:4; Hebrews 10:29).

Liberty of conscience is temporary—not because it is unreal, but because it is purposive.

It endures only while probation remains open. At judgment, liberty does not collapse; it resolves. Its function is not erased but completed. What terminates is not moral agency, but the openness of allegiance (Hebrews 9:27; Luke 13:24–25; Revelation 22:11).

Judgment does not negate freedom; it vindicates it. It proves that choice was real, posture meaningful, and accountability just (Romans 2:6–8; 2 Corinthians 5:10; Ecclesiastes 12:14). The very existence of judgment presupposes that liberty was genuine.

At the appointed time, probation closes and allegiance posture becomes fixed. The invitation ceases not because God withdraws mercy, but because response has reached finality. Liberty is no longer suspension; it has resolved into outcome. Moral agency remains, but the question of allegiance is no longer open (Matthew 25:10–12; Luke 16:26; Hebrews 3:12–15; Revelation 22:11).

This does not represent a loss of freedom, but its consummation.

For the redeemed, liberty is fulfilled as unbroken filial fidelity. In perfect axiology, deontic and modal scaffolds become phenomenologically redundant—not because obedience ceases, but because it no longer requires tension. Alignment is no longer chosen against resistance; it is lived without fracture. Freedom is no longer the capacity to resist, but the joy of unhindered participation in truth (Hebrews 8:10–11; 1 John 3:2; Psalm 16:11; Romans 8:21; Revelation 21:3–4).

This is not a new form of liberty replacing an old one. It is the same moral agency now fully harmonized. What was once chosen under probation is now lived in consummation (Hebrews 12:23; 1 Corinthians 13:10).

For the resistant, liberty ends in exclusion—not retaliation. God does not preserve rebels in being in order to punish them. Life itself is a gift, and refusal of reconciliation culminates in non-participation. This is not coercion extended into eternity, but liberty honored to its final consequence (John 3:16–18; Romans 6:23; Matthew 25:46; Malachi 4:1–3; Nahum 1:9).

Thus eschatology does not undermine liberty of conscience. It completes it (Revelation 20:12–15; Romans 8:18–23).

Liberty of conscience is not a political achievement, a civic compromise, or a psychological artifact. It is the necessary moral space created by a reconciliation already completed, in which no penalty remains to be leveraged and therefore no coercion can be justified (John 19:30; Hebrews 10:10–14; Romans 8:1; Galatians 5:1).

Where conscience is coerced, atonement has been denied. Where belief is enforced, covenant has been abandoned. Where performance is monitored, posture has been displaced (Galatians 2:21; 2 Corinthians 3:6; 1 Samuel 16:7).

Neutrality is exposed as fraud, because no conscience is ever neutral (Romans 1:18–21; Matthew 12:30). History’s attempts to redefine liberty—as right, toleration, or preference—have all failed because they severed freedom from its ontological ground (Judges 21:25; Proverbs 14:12; Isaiah 5:20).

Liberty of conscience stands upstream of every counterfeit neutrality. It is the condition that makes responsibility intelligible, judgment just, and faith meaningful (Deuteronomy 30:19; Romans 2:6–8; Hebrews 11:6). And when judgment comes, liberty is not erased but confirmed: in the redeemed, as unbroken participation in truth; in the rebellious, as the justice of exposure (Revelation 22:11; Matthew 25:31–46; Romans 8:21).

Thus liberty of conscience is neither sentimental nor optional. It is the axis upon which eternity divides—and the silent witness that reconciliation was, in fact, finished (Hebrews 9:27; John 3:16–18; Revelation 20:12–15).